April/May 2013 - Vol. 67

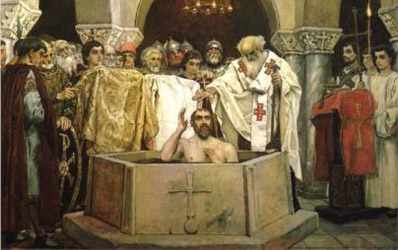

The time is the evening of Easter, somewhere toward the end of the second century A.D. The place is the city of Rome. Christians are gathering together from all over the city to celebrate the true passover, the resurrection of the Lord. In the capital of the ruler of the known world, they gather to honor the true ruler of the universe and the passing away of “this world,” the fallen state of the human race. While the Christian community keeps the vigil that marks the passage of Christ from death to life, new converts gather to be initiated. They have come to believe in Christ; they have been instructed in what it means to live as a Christian; they have turned away from serious sin. Now they are ready to be baptized and to take their places as full members of the Christian people. These new Christians come from all sections and all strata of Roman society, men and women alike. There are hundreds of them, because Rome is a great city. Together, their presence is a testimony to the hunger of the human race for redemption and to the reality of the new life witnessed to by Christians of all kinds. One by one the new converts are brought into the place of baptism. They are separated by sex. As they enter, they put off their clothes as a symbol of putting off their old ways of life. They turn to the West, the place from which they have come, and renounce Satan. They then turn around and face East, the direction from which they believe Christ will come the second time and also the direction of the assembled Christian community, keeping vigil in faith in Christ. The new converts then profess their own faith in the one God, his only Son, and his Holy Spirit.  They are then led into the baptismal pool. As they are covered with water, they are baptized in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The baptismal waters pass over them, signifying the flood of judgment that destroys the old, fallen human being and signifying the death they die with Christ to the old life and the birth to the new. As they emerge from the pool, they are anointed with oil, signifying their consecration through the gift of the Spirit. They are given white garments to wear, a symbol of the new life they will live. As the sunrise begins, itself a symbol of the risen Christ, the new converts enter the assembly of the Christian people. There they celebrate together the Eucharist or Lord’s Supper in honor of his resurrection. When the new Christians take part in communion for the first time, they are also given a cup of milk and honey, symbol of their entry into the promised land of the new life in Christ. This description of the baptismal service of the early Christian community is drawn from the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus. The ceremony itself vividly represents the transition of the convert from the old life to the new life in Christ. Because the baptismal ceremony occurs while the Christian community is celebrating the passage of Christ from death to life, it witnesses to the way the death and resurrection of Christ makes possible the transition of the convert to new life.

To help us understand this transition, we will use the imaginary example of one of those Roman converts who takes part. His name is Gaius, a veteran of the Roman army. He was a man of some strength of character and personal capacity. Over the years, he has not been very scrupulous about whether the disorderly people he killed really deserved death, nor whether the taxes he demanded were strictly due. As a Roman soldier, Gaius had regularly sacrificed to idols to ensure personal protection and success in military operations. He had regularly engaged in what Christians consider adultery while away from his wife. As a veteran who had been honorably discharged at the end of his term of service, he was an eminently respectable man according to Roman custom. According to the old covenant law, however, he should have been a candidate for execution himself. Gaius came into contact with Christians when he settled down after leaving the army. They were a conspicuous group, friendly and helpful, but living lives that were disciplined in a way his was not. At the invitation of one of these believers, Gaius attended sessions conducted by a Christian teacher. He learned about the truly wise way to live, about the only true God, and about the Son of God who came to bestow immortality. Gaius believed what was said and presented himself to become a Christian. Considering an example like Gaius allows us to focus on how an individual is redeemed without raising many ecumenical issues. He is an adult pagan with a record of seriously sinful actions that need to be forgiven and a way of life from which he needs to be freed. He is not an infant, a young person raised in a good Christian family, or a nominal Christian without many signs of spiritual life. All such cases would raise some ecumenical divergences. We are also going to consider Gaius at the point when he leaves paganism and is joined to Christ – not at the last judgment or at a point when he might fall into serious sin and be restored. Such cases would also raise some ecumenical divergences. Finally, we are not going to raise questions about the relationship of conversion and baptism in the transition from paganism to Christianity, because this will also raise some differences. We will simply look at the transition itself. In this final chapter, then, we will consider the way redemption comes

to those who turn to Christ. We will then raise the question of how fully

Christ reverses the fall for those who believe in him now and how much

we have to wait for, since we are saved in hope (Rom 8:24). This chapter

will not describe a further benefit of Christ’s redeeming work, but will

complete the picture by looking at how forgiveness and new life come to

those who turn to Christ.

The Transition There are several ways in which the New Testament describes the transition Gaius underwent in order to become a Christian. They can all be related to a judicial understanding, a ceremonial understanding, and a personal transformational understanding. We will first consider the aspect of his transition that is described in Scripture and much of Christian teaching using judicial terms. Gaius was released from the entire penalty due to sin. He had deserved or merited the sentence of condemnation by his own actions. He was also subject to the penal consequences due to the state of the human race, the way anyone shares in the consequences of the actions of the group to which they belong. To some extent, he personally deserved those as well, partly by his role in furthering the sinful condition of the race, partly in simply not deserving anything better. Those penal consequences included both the kind of death he would undergo at the end of his life as well as the spiritual death he was in as a pagan. Gaius needed to be freed from the consequences of his sinful state. This required redemption from his “debt of punishment”, that is, the way in which those consequences were due to him. Scripture, as we have seen, most commonly describes that freeing as forgiveness of or release from sins. It also describes it as “justification”, a word primarily used by Paul or those associated with him and picked up by later Christian teachers. There is debate over the meaning of the word “justification” as used in Scripture. Some hold that the word means being made just or righteous in the sense of being changed in character. Others hold that it means giving new life. Others hold that it means forgiving or pardoning guilt. Almost all would agree that it concerns restoration to right relationship with God. These different meanings are not necessary mutually exclusive. Since, however, “to justify” often meant in scripture to acquit those who have been charged with wrongdoing, the use of the word in contexts concerned with becoming a Christian was probably at least partly based upon the idea of a judge acquitting a defendant. Since Gaius was not innocent when he became a Christian, God, the judge, did not say that his previous life was acceptable or that he did not deserve punishment. Rather, God simply said that he was freed from punishment and from the debt of punishment. This process was like acquitting a defendant rather than condemning him. It meant that Gaius was granted life rather than condemned to death. In this sense Gaius was justified by the supreme Judge. We would be more likely to use the word “pardon” for what happened to Gaius. Paul probably used the word that means acquittal to emphasize the fact that Gaius was freed because of what Christ did. In his sufferings and death, the death of a righteous, innocent man, obedient to God, Christ underwent a punishment that God accepted instead of the one Gaius deserved. To use the technical theological term, Christ made satisfaction for Gaius so that no penalty was due to him anymore, especially not the death penalty. He was released to life. Consequently, once justified, Gaius was in a good or right relationship with God, treated by God as a just or innocent man. In short he was acquitted because no penalty was due to him, although not because his actions deserved it but because of what had been done for him by another. The second understanding of the transition Gaius underwent in becoming a Christian is ceremonial. While the judicial understanding focuses on the release from the obstacle in the way of Gaius’ new life, the ceremonial understanding includes the way Gaius was positively established in that new life as well. In both old and new covenant teaching sin is understood to be a kind of uncleanness or impurity that defiles sinners. Unclean people or things are unfit to be in God’s presence and cause offense to God when allowed to be in his presence. Therefore, someone like Gaius had to be cleansed in order to be put into a condition where he could come into God’s presence, that is, enter into a relationship with God that involved any closeness or direct access. At the same time, the positive side of what happened to Gaius is also described in ceremonial terms. When he became a Christian, he was not only cleansed but also consecrated or sanctified or made holy, to use three different translations of the same word. Christians are made holy the way a sacrifice is, the way a temple is, and the way a priest is. As sacrifices, they have been given to God or made over to God for his honor or glory (Romans 15:16). As temples, they are places in which God dwells and in which he is glorified (1 Corinthians 6:19-20). As priests, they have access to God so that they may come into his presence and worship him (Ephesians 2:18). Therefore, Christians are holy. They belong to God, are set apart for him, with access to him. They are filled with his presence, and as a result they are like God and have a similar character or holiness of life to his own (1 Peter 1:14-16). The third understanding of the transition Gaius underwent is the personal transformational one. He went from death to life, and in the process he was made a new kind of human being. The focus here is on the result, the new life, not on the release from sin that is the necessary precondition. But the New Testament presents this transition as closely tied up with freedom from sin. Gaius was dead because of sin, since sin itself is destructive of life and since it cuts people off from the source of true life, God himself. A number of passages concerning the death of Christ also concern the transition of human beings from death to life by becoming a Christian. They assert in one way or another that Christians have died in or with Christ and that that “death” has produced a new life in them. “We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death so that…we too might walk in newness of life” (Romans 6:4). “You were buried with him in baptism, in which you were also raised with him… You, who were dead in trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, God made alive together with him” (Colossians 2:12-13). There are many similar passages, almost all in Pauline writings. These passages can only be understood in light of what it means to be in Christ. Gaius can be said to have died “with Christ” because he was joined to him and left behind his old life. He can be said to have risen “with Christ” because he received new life in him. In other words, Gaius left behind the old kind of human existence and became a new kind of human being. To describe this as dying and rising is to emphasize the radical nature of the change. The change is so great, in fact, that Paul understands it as giving Christians a new identity, at least in the eyes of God. The old Gaius has ceased to exist. As a consequence, he no longer has to live according to obligations contracted in his previous life, at least his “spiritual” obligations (Romans 7:1-6). As a new person in Christ, he is freed from the past. The change is great enough to be described as death. Gaius died to the life he had before. Even more he, along with all other Christians was “buried…with him by baptism into death”. That does not mean that he killed himself. He was put to death by another, God, and put to death so completely that he was also buried. In short, the death penalty was inflicted upon him, but inflicted on him in such a way that he was freed from the old person he was and the sinful nature that characterized that old person, and reborn into a new life. Because Gaius is now in Christ he can share in the results of Christ’s death, resurrection, and ascension. To say that when he became a Christian Gaius died, rose, and ascended with Christ does not mean that Gaius went back in time and joined Christ on the cross. Nor does it mean that Christ died a second time (or a millionth time) at the point of Gaius’ conversion or baptism so Gaius could die with him. Rather, it means that Gaius became identified with Christ when he became a Christian. Because of this personal union, Christ’s past became his own past and the benefits of what Christ did became his own inheritance. To say Gaius died, rose, and ascended with Christ means that he is incorporated into the one who died, rose, and ascended. Now he can be treated as one to whom those events happened and properly share in what those events produced. These three descriptions – condemnation to justification, uncleanness to holiness, and death to life – all describe the same transition from a state of death, uncleanness, and condemnation due to sin to a life of holiness in a reconciled relationship with God. Each is an analogous description. Together they describe what happens when someone becomes a Christian. Christian teachers have a variety of views about how these descriptions go together. These differences cannot be stated adequately without introducing considerations that go beyond the scope of this book. All would agree, however, that the transition to fully becoming a Christian involves a change expressed by the three understandings. Taken together these descriptions speak about a transition that involves both release from the debt of punishment or penalty due to sin and an internal change that gives people the power to live without sin. The two aspects of release and change are spoken about in different terms and related to one another in different ways, but all Christian traditions recognize them. All orthodox Christians recognize that Gaius was helpless to save himself. He was spiritually dead, in slavery without any means to purchase his freedom, under a just condemnation to death. He did not deserve new life, but could only look to the mercy or grace of God. Gaius needed a redeemer. Christ was that redeemer. He paid the price, underwent the punishment, and offered the sacrifice that allowed the debt to be taken away and new life to be given. He also in his own person underwent the process of self-lowering and exaltation that gave Gaius a new kind of life, freed from the power of fallenness. To those who would come to Christ and seek redemption from him, he could give it. He could join them to himself, releasing them from the penalty due to sin and sharing his own life with them by pouring out upon them the Holy Spirit. Gaius needed the grace or mercy of Christ. He did not deserve the new life, but deserved the opposite. He could not earn the new life, but had to turn to Christ to receive it. He did so because he understood from the gospel that Christ was offering it. At the same time, to receive the new life Gaius did not have to do anything other than turn to Christ. To turn to Christ, he had to turn in faith to Christ as his Lord and Redeemer. He had to repent of his sins and his old way of life. He had to be baptized, being joined to the Christ who died and rose and being joined to his body, the church. To consider everything involved in turning to Christ would take us beyond

the topic of this book. Here we can simply say that Christ is the Redeemer,

that Gaius could turn to Christ and be joined to him to receive redemption,

and that once he did, he became a new person.

Already…Not Yet Two Comings

and Redemption

You, who were once estranged and hostile in mind, doing evil deeds, he has now reconciled in his body of flesh by his death, in order to present you holy and unblemished [RSV: blameless] and irreproachable before him. – Colossians 1:21-22Paul is probably speaking here about Christ as a priest because his reconciling work is described in the previous verse as “making peace by the blood of his cross”. Christ is standing “before” God, before the throne of his Father in the heavenly temple and presenting an offering to him. His redeeming work has been completed, and he can now present the restored human race as an offering that truly honors God. The surrounding angelic beings raise the song and blow the trumpets that accompany such an offering, a song both to honor and thank God for what he has done and to proclaim the victory he has won. Paul calls us “holy and unblemished”, words commonly used to describe something consecrated to God. Christ could be presenting us as a body of priests, people who will now be able to be in God’s presence and worship him (1 Peter 2:5; Revelation 5:10; Ephesians 1:4). More likely, he is presenting us as a sacrifice, a gift to God, acceptable to the Lord (Romans 15:16; 12:1; Philippians 2:17). He might be doing both. But in what state are we being offered? Is Christ offering the Christian people who, joined to him, are living holy and unblemished lives before their earthly deaths? Or is he offering the Christian people after his second coming when he presents the kingdom to the Father, when all his enemies are defeated, and when sin and death are completely gone? In this passage from Colossians Christ is here pictured as presenting the members of his body at the end. The next verse indicates that offering will only happen “provided that you continue in the faith, stable and steadfast, not shifting from the hope of the gospel which you heard”. Earthly endurance is necessary for the Christian people to achieve complete victory and fully become God’s possession. But if that is so, what have we received by becoming Christians? Are we even redeemed now or do we have to wait for a future time? Four major events demarcate human history. The first two occur at the beginning: the creation of the human race in the state God wanted and the fall away from that state. The second two events occur at the end. Both could be described as the coming of the Redeemer to raise up the human race from where it has fallen. Christ came the first time “at the end of the age to put away sin”. Some day he will come again “to save those who are eagerly waiting for him” (Hebrews 9:26-28). Each of his comings is a redemption, a freeing from bondage. Each of his comings is a raising up of the human race and a giving of life. It can be difficult to tell whether particular Scripture passages are referring to the results of the first coming or the second coming. They are purposely described in much the same words. Scripture scholars at times use the phrase “already…not yet” to describe the relationship between the two. There is only one redemption that is given to us through the two comings of Christ, so that we already have it to some extent, but do not yet have it in its full extent. What Christians are given after the first coming is the same reality that they will have after the second coming: justification, union with God, holiness, victory, and freedom. The pardon or freedom from condemnation we receive now is the same one we will have at the last day. We will be found “in him” with a righteousness or justification that comes through faith in him (Phil 3:9). The new life we have now is the same life we will have at the last day. “When Christ who is our life appears, then you also will appear with him in glory” (Colossians 3:4). “We know that when he appears, we shall be like him” (1 John 3:2). We do not have to wait until the last day for redemption to come. We already experience the life of the age to come. Even now the presence of the Spirit in our hearts is a down payment or first installment (Ephesians 1:14; 2 Corinthians 5:5) of what is to come. The Spirit himself bears witness to our spirit that we are children of God (Romans 8:16). As some Christian teachers have put it, we have an assurance through faith that we have already received the relationship with God that will be ours in the age to come. Yet there is certainly a difference between what we are experiencing now and what we will experience after the second coming. Although for Christians the age of this fallen world has already passed away so that they now live in the age of the new creation, the old has not yet completely passed away and Christians are not completely free of it. To experience the full results of the redemption, they will have to persevere until a further deliverance comes. Redemption

Now

To begin with the success, those who have received the risen Christ after his first coming have already been given new life fully enough to achieve the purpose of human beings. The reversal of the defeat and ruin of the human race as a whole has already occurred. It is now possible for human beings to be freed from sin and live in friendship with God. Those who “continue in the faith…not shifting from the hope of the gospel” will some day make up the human race as God originally intended it to be. At the end the redeemed race will be everything God planned it to be in the beginning. The passage in Colossians states that we will be “holy and unblemished”, blameless with the holiness of an offering that is truly acceptable to God. That means that the redeemed race will be in a good relationship with God, living the way God intended it to live. Paul implies that this description can also be true now when he exhorts the Philippians to be “blameless and innocent, children of God without blemish in the midst of a crooked and perverse generation, among whom you shine as lights in the world, holding fast the word of life, so that in the day of Christ I may be proud that I did not run in vain or labor in vain” (Philippians 2:15-16). The very fact that he needs to exhort them indicates that they need to persevere in living a life pleasing and acceptable to God, but it also implies that it is possible to do so. Ephesians even uses the Colossians phrase “holy and unblemished”, but probably applies it to our life now as priests to God (Ephesians 1:4; 5:27), indicating that such a state is possible here on earth. Christians, then, can live a life that is pleasing to God as the result of the redemption. They can not only be freed from the guilt of sin, but also from the power of sin. That means at the least that it is possible for Christians to live free from the kind of serious wrongdoing that would lead to their being ineligible to inherit the kingdom of God (1 Corinthians 6:9-10; Galations 5:21). It does not mean, however, that they can be free from all defects in the way they live, much less completely free from their fallenness or “flesh”. It also does not mean that they will necessarily be heroic or even outstanding in virtue. The claim that Christians can live a life pleasing to God is a somewhat modest claim. It simply means that they need not murder people nor deliberately cause serious injury, that they need not steal, rob, or defraud people of significant financial or material possessions, and so on. It also means that they will worship God, observe the Lord’s Day or sabbath, support their parents in old age, and so on. Although some fail, many do live in such a way. Freedom from such serious sin may not be a high standard. The claim, however, that Christians do live such lives is a claim of immense importance. It means that in Christ the human race can live in a way that achieves the purpose for which it was created – imperfectly perhaps, but truly. It also means that the human race is on the road to bringing all of creation to where God wants it to be. The Two Stages

I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us. For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God; for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will, but by the will of him who subjected it in hope; because the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and obtain the glorious liberty of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning in travail together until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies. For in this hope we were saved. – Romans 8:18-24

For our purposes, the passage is more notable for the way it describes the two stages in the life of Christians. They now have the first fruits of the Spirit; they will some day receive the full harvest. They now have the spirit of adoption who makes their spirits know that they are sons of God; they will some day “come of age” and be able to fully live as sons of God. They now, in other words, have to some extent what they will some day receive fully. The change will happen in an event Paul here describes as “the redemption of our bodies”. Paul seems to be contrasting here what will happen to our bodies with what has happened to our spirits (Rom 8:16, 23). Elsewhere he speaks about what will happen to “the outer man” in contrast with what has happened to “the inner man” (2 Cor 4:16). In brief, the writings of Paul teach that through the first redemption, something changed inside of us. This change has liberated us so that we can live in a new way, be in a good relationship with God, and not be under the domination of sin. Only in the future will we be changed in such a way that we will be able to enjoy the fullness of the life God intends. Redemption has rescued the human spirit, in Paul’s terms, the ultimately controlling element in how we act, but it has not yet liberated “the body”. We therefore now live in a “body” that is still part of the fallen world and consequently is still to some extent determined by it. We are subject to physical decay, disease, and death. Fallenness also affects us in nonphysical ways. We still live “in the flesh”, the fallen nature. We still experience what Western Christian teachers, using a Latin translation of a scriptural word, have often termed “concupiscence”, the desires that come from the fallen human state. These desires are not just disordered bodily desires; they are also disordered “desires…of mind” (Eph 2:3). They do not need to prevail since we are no longer enslaved to them (Rom 6:12-14). But such desires will not be gone until the physical body dies and is glorified, and consequently they affect our ability to live the life of Christ as well as we may desire. The fallen world around us also affects the way our lives go. While Satan has truly been defeated, he has not yet lost all hold on most of the human race or on most human events. Those who have not yet been redeemed in Christ are still “following the course of this world, following the prince of the power of the air, the spirit that is now at work in the sons of disobedience” (Eph 2:2). Satan’s action makes the fallen world a place where God’s rule is not acknowledged. Consequently, much of what happens to us here and now is more like Christ’s path to the cross than like his glorious resurrection triumph. In the crucifixion and resurrection Christ has won the victory over Satan, but the effects of the victory likewise come in two phases. At his first coming, those who believe in Christ are “delivered…from the dominion of darkness and transferred…to the kingdom of [God’s] beloved Son, in whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins” (Colossians 1:13-14). At his second coming, Christ will “put all his enemies under his feet” (1 Corinthians 15:25), and the devil, along with death and Hades, will be “thrown into the lake of fire” (Revelation 20:10, 14). In between, much the same is true of the external source of sin, Satan and “the world”, as of the internal source of sin, the “flesh” or our fallen desires. We are free from them “in the inner man”, but subject to them “in the outer man”. Satan can hinder us (1 Thessalonians 2:18) and keep us from achieving what God wants us to achieve. He can harass us (2 Corinthians 12:7), cause us to fall sick, persecute us, and even put us to death. We confront Satan in our weakness just as Christ did on the cross, with bodies that have not yet been glorified (2 Corinthians 12:9-10; 13:4). We live in a time of spiritual warfare. Like Christ, we have to be prepared for suffering, defeat, and death. Those “enemies” come our way simply as the result of the weakness of our fallen natures, but are also inflicted on us by the evil one, especially as we seek to free others from his dominion. Yet our inner man has genuinely been delivered. We are free from Satan and the world. He cannot destroy our good relationship with God or make us sin – unless we, like Adam and Eve, give in to temptation and choose to follow him. “Provided we continue in the faith, stable and steadfast,” we are safe from him. Even more, we are not just helpless in the face of Satan’s attacks, but we can deal with them by the power of God because we live with Christ (2 Corinthians 13:4). Christ has taken up residence in us in the midst of this fallen world. His death on the cross has already won a great victory, only not yet a complete victory. The correct balance in our understanding of the “already” and the “not yet” is difficult to achieve. Some Christians are so centered on the “not yet” that they do not seem to have gotten much past the cross. They experience no genuine freedom from sin, no operation of resurrection power in healing and miracles, and little victory other than endurance. Life is simply a vale of tears, a way of the cross. Some Christians, on the other hand, are so centered on the “already” that they believe the full transformation can be realized now, that they cannot sin, the sons of God can already be manifested, all diseases can be healed, and all satanic attacks can be ordered away. Such views are less common but in various combinations have been held throughout the centuries. The truth does not lie somewhere in between the already and the not yet as a kind of compromise. It lies in seeing that both are true at the same time. We are already/not yet redeemed. The victory of Christ is already/not yet accomplished. In other words, we have resurrection life but live it in fallen bodies in a fallen world. Even though the victory is incomplete, the most important part of it has already been won. The results of the second phase of redemption will surpass the first in regard to what most preoccupies fallen man. What has not yet happened – full immortality, freedom from pain, suffering, disease, and frustration – seems to fallen human beings more momentous. But in regard to what most preoccupies God, and hopefully those who have come to living faith in Christ, the first phase of redemption is much more important – release from sin, new life in Christ, and a good relationship with God. The realities of the redeemed life are important in themselves, but they also make possible the benefits that come with the second phase of redemption. Only those who have been joined to the Redeemer in this life will experience the full deliverance he will bring in the age to come. We are warned not to “be conformed to this world” but to be “transformed by the renewal of our minds”. As this happens, we will begin to see reality with the wisdom of God and so know what is truly good (Romans 12:2) living in the light of the age to come.

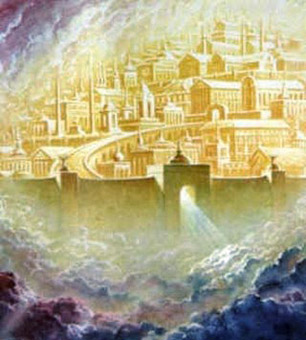

The Consummation The last pages of the Scriptures contain a vision of the end of human history. It is the end not simply in the sense of a conclusion but in the sense of a completion. As a mature tree brings to completion the process begun with planting the seed, this final vision presents the completion of what was planted in this world by Christ’s victory. An end can be the cause of what comes earlier in time. What an architect envisions as the final building produces and unifies the process of construction. In such a way, the vision of the new Jerusalem, the completed human race, is the motive force of history, because God follows it as he brings human history to its completion. John is taken to a “great, high mountain” (Revelatiob 21:10) by one of the angels who brought the seven last plagues. Because this mountain is the successor to Sinai, to Zion, to Eden, it is the highest mountain on earth (Isa 2:2). Next to this mountain, Everest is insignificant. This is the mountain of God. As John looks, he sees the new Jerusalem, the city of God coming down out of heaven. It is not built up by human means, no tower of Babel reaching up to heaven. The holy city comes from heaven to earth. The new Jerusalem is grace from God, a dwelling place not claimed and established by human beings but given to them by God. A jewel beautiful in substance and shape, pure gold, a perfect cube like the holy of holies, this new city is a reflection of the glory of God. Because sin has passed away, weakness, corruption, and defectiveness no longer keep creation from being a transposition of God’s glory into a new medium. In a way we can now only dimly perceive in the created world around us, the beauty and goodness and truth of the new Jerusalem will be a clear reflection of God’s own beauty and goodness and truth. The new Jerusalem will have no temple. The holy city itself will be a temple, filled with the presence of God, the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb. The presence of God will not be found in a special place or building, but will be mediated to the whole city by the Lamb. He will be the lamp, the translucent being from which streams the glory of God. Like a good lamp, the light he provides will be brilliant without being blinding. The Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are enthroned together in the city. They are one in their reign, under which human history can finally fulfill its purpose. God’s will is done on earth as in heaven. From that throne, the symbol of that reign, comes life. Simply to be united to God, to be under his reign, is to receive life. The Holy Spirit, the water of life, flows into this new creation from the Father through the Son. The city of God is paradise restored, the place where life is unmixed delight. By the river of the water of life grows the tree of life, bringing healing and restoration for those who have been wounded by sin. In the New Jerusalem, it is no longer the human race that is banished, but the curse that is banished. The flaming sword of God’s wrath is gone, quenched by the blood shed on the cross, and paradise is now opened. The human race has returned home. There human beings see God the Father face to face, and to see him is happiness itself. In his presence, filled with his life, in his image and likeness, they reign over material creation and make it a temple to the glory of God.

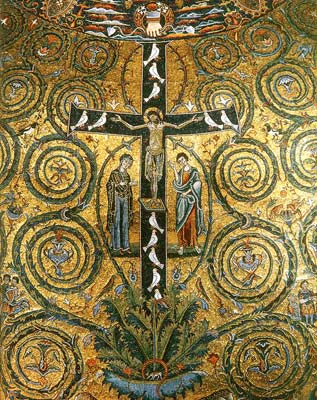

This final vision of human life brought to its completion is not essentially different than what God had in mind when he first created the human race. Yet the new Jerusalem will not be the simple unfolding of a well-tended, protected seed to its complete development. The holy city of God had to be attained by a redemption that cost the blood of the Son of God himself. It is the Lamb who has been slain from whose face the glory of God streams and from whose throne the water of life flows. Early Christian pictures depict the cross of Christ as a tree with its branches filling the city of God. These pictures make explicit what is implicit in the vision of the new Jerusalem. The tree of life was replanted in the midst of the human race when Christ was lifted up on the tree of the cross. By his death he made new life possible. In his resurrection, the cross sprouted, and its branches filled the whole earth. At the end of time, those who have eaten the fruit of that tree will be the citizens of the new Jerusalem.

Steve Clark is a founder and former president of the Sword of the Spirit, a noted author of numerous books and articles, and a frequent speaker. This article is excerpted from chapter 12 of Steve Clark’s Book, Redeemer: Understanding the Meaning of the Life, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ, copyright © 1992, 2013. Used with permission.. |

. | |

|

publishing address: Park Royal Business Centre, 9-17 Park Royal Road, Suite 108, London NW10 7LQ, United Kingdom email: living.bulwark@yahoo.com |

. |