“The way

to God lies

through love of

people” -

Mother

Skobtsova

Born

into a family of aristocratic Russian

landowners in 1891, Elizaveta (Liza)

Iur’evna Pilenko trod a long and difficult

path from her birthplace near the Black Sea

to her martyr’s death in one of Hitler’s

concentration camps. During her adolescence,

Liza rejected her Orthodox religious faith.

While at the university in St. Petersburg,

she was involved with an avant-garde

literary circle and later published two

volumes of poetry. She married impetuously

at eighteen and soon divorced. During the

turmoil following the Bolshevik Revolution,

Liza, with her mother, her daughter Gaiana,

and her second husband Daniil Skobtsov, fled

Russia and eventually settled in Paris in

1922.

With the death of Liza’s youngest daughter

Nastia in 1926, she rediscovered faith in

God and saw a “new road before me and a new

meaning in life... to be a mother for all.”

She sought out destitute Russian refugees in

hospitals and mental asylums and in the

slums to help them, saying, “They have no

need of sermons; they need the most basic

thing of all, compassion.”

In 1932, when she was forty-one years old,

Liza received a marital separation, which

was authorized by the Orthodox Church

because of her decision to enter the

monastic life. She made her profession as an

Orthodox nun under the guidance of

Metropolitan Evlogii, who gave her her new

name, Maria, in memory of St. Mary of Egypt.

“Like this Mary, who lived a life of

penitence in the desert,” Evlogii told

her, “go and act and speak in the

desert of human hearts.” Later he wrote of

her: “When she took the veil she brought as

a gift to Jesus all her talents. Among them,

a true gift of God, was the knowledge how to

approach those who had lost the right path

without despising their weaknesses and

faults.”

After visiting Orthodox convents in Estonia

and Latvia, Mother Maria was convinced that

a new form of monasticism was required to

meet the needs and circumstances of the

Russian émigrés in France. Back in Paris,

she lived as a “monastic in the

world,” pushing the borders of monasticism

past their former limits—and sometimes

disturbing the more traditionally-minded as

she did. Her monastery was the world around

her, where she sought to soothe human

suffering in any way that she encountered

it, recognizing that “each person is the

very icon of God incarnate in the world.”

Mother Skobtsova's small

house of hospitality in Paris

Mother Skobtsova's small

house of hospitality in Paris

Soon Mother Skobtsova

opened a small house of hospitality for

the needy, trusting God to provide the

funds for it. In 1934, the work was

transferred to a larger house at 77 rue

de Lourmel, where she provided meals and

a place to sleep for the hungry and

homeless. The house, with its drawing

room and a chapel adorned with

embroidery and icons from Maria’s

talented hand, also served as a meeting

place for intellectual Russian Orthodox.

Over the following years, she opened

another hostel for the destitute and a

sanatorium for the ill while she herself

lived in a small, unheated room.

On June 14, 1940, Paris fell to the Nazis.

Mother Maria joined some colleagues in

preparing and dispatching food parcels and

funds to families of more than 1,000 Russian

émigrés who were imprisoned by the Nazis.

She also hid Jews at Lourmel and forged

documents for them. In 1942, 6,900 Jews were

rounded up and kept for five days in the

Velodrome d’Hiver, Paris’ sports stadium,

with only one water faucet and ten latrines.

She managed to enter the stadium and,

assisted by garbage collectors, smuggled out

several Jewish children in garbage bins.

In February 1943 Mother Maria, her son Iura,

and Lourmel’s chaplain, Father Klepinin,

were arrested. In response to the accusation

that Maria was helping “yids,” her mother

Sophia told the Gestapo agent: “My daughter

is a genuine Christian, and for her there is

neither Greek nor Jew, only individuals in

distress. If you were threatened by some

disaster, she would help you too.”

Klepinin and Iura died in Dora concentration

camp. Mother Maria was deported to

Ravensbrück concentration camp. There, as

prisoner Number 19263, she continued her

ministry among her companions, with the

strength of her faith giving them

encouragement and love in the midst of

hopelessness and despair. Finally, Maria,

her health broken, could no longer pass the

roll call on Good Friday 1945. She stepped

into the line with those women condemned to

die, hoping to inspire them to meet their

fate with faith in God. As one witness

wrote, “She offered herself consciously to

the holocaust . . . thus assisting each one

of us to accept the cross. . . . She

radiated the peace of God and communicated

it to us.”

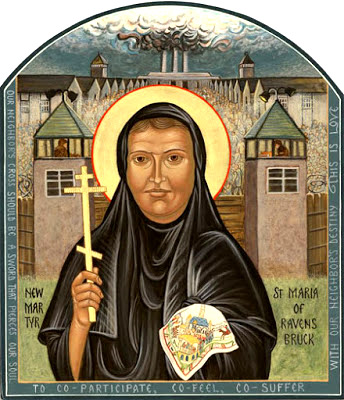

Icon of Maria Skobtsova - martyred

at Ravensbruck concentration

camp

Mother Maria Skobtsova was gassed on Holy

Saturday. Ravensbrück’s women prisoners from

France were liberated through the auspices

of the International Red Cross on Easter

Sunday.

Anthony Bloom, Orthodox Metropolitan of

Sourozh and Great Britain, noted that Mother

Maria is remembered in the context of her

times—the Russian Emigration, the French

Resistance, and the Nazi concentration

camps. However, he added, “her achievement

extends beyond the circumstances of her

life, and it outlives them. Since her life

was completely interwoven with the destiny

of her contemporaries, their turmoil was

hers, their tragedy was hers. And yet she

was not swept away by it. She was anchored

in God and her feet rested on the Rock.”

From the writings

of Mother Maria

What is most

essential, most determining

in the image of the cross is

the necessity of freely and

voluntarily accepting it and

taking it up. Christ freely,

voluntarily took upon

Himself the sins of the

world, and raised them up on

the cross, and thereby

redeemed them and defeated

hell and death. To

accept the endeavor

and responsibility

voluntarily, to freely

crucify your sins - that is

the meaning of the cross,

when we speak of bearing it

on our human paths.

Freedom is the inseparable

sister of

responsibility. The

cross is this freely

accepted responsibility,

clear-sighted and

sober.

(Essential

Writings, p. 64)

The way

to God lies through love

of people. At the

Last Judgment I shall

not be asked whether I

was successful in my

ascetic exercises, nor

how many bows and

prostrations I

made. Instead I

shall be asked, Did I

feed the hungry, clothe

the naked, visit the

sick and the

prisoners. That is

all I shall be

asked. About every

poor, hungry and

imprisoned person the

Savior says "I:" "I

was hungry, and thirsty,

I was sick and in

prison." To think

that he puts an equal

sign between himself and

anyone in need... I

always knew it, but now

it has somehow

penetrated to my sinews.

It fills me with awe.

|

This

article is adapted from the book, Even

Unto Death: Wisdom from Modern Martyrs,

edited by Jeanne Kun, The Word Among Us

Press, ©

2002. All rights reserved. Used with

permission.