December

2014/January

2015 - Vol. 77e

Jesus

heals a lame man, by James Tissot

.

The

Prayer of the Ever-Living Christ

.

By Edith

Stein (1891-1942)

The prayer of the church is

the prayer of the ever-living Christ. Its

prototype is Christ's prayer during his

human life.

Jesus' public prayer

life

The Gospels tell us that

Christ prayed the way a devout Jew faithful

to the law prayed. Just as he made

pilgrimages to Jerusalem at the prescribed

times with his parents as a child, so he

later journeyed to the temple there with his

disciples to celebrate the high feasts.

Surely he sang with holy

enthusiasm along with his people the

exultant hymns in which the pilgrim's joyous

anticipation streamed forth: "I rejoiced

when I heard them say: Let us go to God's

house" (Psalm 122:1).

From his last supper with

his disciples, we know that Jesus said the

old blessings over bread, wine, and the

fruits of the earth, as they are prayed to

this day. So he fulfilled one of the most

sacred religious duties: the ceremonial

passover seder to commemorate deliverance

from slavery in Egypt. And perhaps this very

gathering gives us the profoundest glimpse

into Christ's prayer and the key to

understanding the prayer of the

church.

While they were at supper,

he took bread, said the blessing, broke the

bread, and gave it to his disciples, saying,

"Take this, all of you, and eat it: this is

my body which will be given up for

you."

In the same way, he took the

cup, filled with wine. He gave you thanks,

and giving the cup to his disciples, said,

"Take this, all of you, and drink from it:

this is the cup of my blood, the blood of

the new and everlasting covenant. It will be

shed for you and for all so that sins may be

forgiven."

Blessing and distributing

bread and wine were part of the passover

rite. But here both receive an entirely new

meaning. This is where the life of the

church begins. Only at Pentecost will it

appear publicly as a Spirit-filled and

visible community. But here at the passover

meal the seeds of the vineyard are planted

that make the outpouring of the Spirit

possible.

In the mouth of Christ, the

old blessings become life-giving words.

The fruits of the earth become his body and

blood, filled with his life. Visible

creation, which he entered when he became a

human being, is now united with him in a

new, mysterious way. The things that serve

to sustain human life are fundamentally

transformed, and the people who partake of

them in faith are transformed too, drawn

into the unity of life with Christ and

filled with his divine life.

The Word's life-giving power

is bound to the sacrifice. The Word

became flesh in order to surrender the life

he assumed, to offer himself and a creation

redeemed by his sacrifice in praise to the

Creator.

Through the Lord's last

supper, the passover meal of the Old

Covenant is converted into the Easter

meal of the New Covenant: into the

sacrifice on the cross at Golgotha and those

joyous meals between Easter and Ascension

when the disciples recognized the Lord in

the breaking of bread...

Jesus'

solitary prayer life

We saw

that Christ took part in the public and

prescribed worship services of his people, i.e.,

in what one usually calls "liturgy." He brought

the liturgy into the most intimate relationship

with his sacrificial offering and so for the

first time gave it its full and true meaning

that of thankful homage of creation to its

Creator. This is precisely how he transformed

the liturgy of the Old Covenant into that of the

New.

But Jesus

did not merely participate in public and

prescribed worship services. Perhaps even more

often the Gospels tell of solitary prayer in the

still of the night, on open mountain tops, in

the wilderness far from people.

Jesus'

public ministry was preceded by forty days and

forty nights of prayer. Before he chose and

commissioned his twelve apostles, he withdrew

into the isolation of the mountains.

By his

hour on the Mount of Olives, he prepared himself

for his road to Golgotha. A few short words tell

us what he implored of his Father during this

most difficult hour of his life, words that are

given to us as guiding stars for our own hours

on the Mount of Olives. "Father, if you are

willing, take this cup away from me.

Nevertheless, let your will be done, not mine."

Like

lightning, these words for an instant illumine

for us the innermost spiritual life of Jesus,

the unfathomable mystery of his God-man

existence and his dialogue with the Father.

Surely, this dialogue was life-long and

uninterrupted.

Christ

prayed interiorly not only when he had withdrawn

from the crowd, but also when he was among

people. And once he allowed us to look

extensively and deeply at this secret dialogue.

It was not long before the hour of the Mount of

Olives; in fact, it was immediately before they

set out to go there at the end of the last

supper, which we recognize as the actual hour of

the birth "Having loved his own..., he loved

them to the end."

He knew

that this was their last time together, and he

wanted to give them as much as he in any way

could. He had to restrain himself from saying

more. But he surely knew that they could not

bear any more, in fact, that they could not even

grasp this little bit.

The

Spirit of Truth had to come first to open their

eyes for it. And after he had said and done

everything that he could say and do, he lifted

his eyes to heaven and spoke to the Father in

their presence.

We call

these words Jesus' great high priestly prayer,

for this talking alone with God also had its

antecedent in the Old Covenant. Once a year on

the greatest and most holy day of the year, on

the Day of Atonement, the high priest stepped

into the Holy of Holies before the face of the

Lord "to pray for himself and his household and

the whole congregation of Israel."

He

sprinkled the throne of grace with the blood of

a young bull and a goat, which he had previously

to slaughter, and in this way absolved himself

and his house "of the impurities of the sons of

Israel and of their transgressions and for all

their sins."

No person

was to be in the tent (i.e., in the holy place

that lay in front of the Holy of Holies) when

the high priest stepped into God's presence in

this awesomely sacred place, this place where no

one but he entered and he himself only at this

hour. And even now he had to burn incense "so

that a cloud of smoke...would veil the judgment

throne...and he not die." This solitary dialogue

took place in deepest mystery.

Day of Atonement - Most Solemn

Day of Prayer

The Day

of Atonement is the Old Testament antecedent of

Good Friday. The ram that is slaughtered for the

sins of the people represents the spotless Lamb

of God (so did, no doubt, that other chosen by

lot and burdened with the sins of the people

that was driven into the wilderness). And the

high priest descended from Aaron foreshadows the

eternal high priest.

Just as

Christ anticipated his sacrificial death during

the last supper, so he also anticipated the high

priestly prayer. He did not have to bring for

himself an offering for sin because he was

without sin. He did not have to await the hour

prescribed by the Law and nor to seek out the

Holy of Holies in the temple.

He

stands, always and everywhere, before the face

of God; his own soul is the Holy of Holies. It

is not only God's dwelling, but is also

essentially and indissolubly united to God.

He does

not have to conceal himself from God by a

protective cloud of incense. He gazes upon the

uncovered face of the Eternal One and has

nothing to fear. Looking at the Father will not

kill him. And he unlocks the mystery of the high

priest's realm.

All who

belong to him may hear how, in the Holy of

Holies of his heart, he speaks to his Father;

they are to experience what is going on and are

to learn to speak to the Father in their own

hearts.(24)

[Excerpt

from The Collected Works of Edith

Stein, translated by Waltraut Stein,

© 1992 ICS Publications. See online

collection at Kolbe

Foundation]

Article, Blessed by

the Cross, by Jeanne Kun is

excerpted from the book, Even

Unto Death: Wisdom from Modern Martyrs,

edited by Jeanne Kun, The

Word Among Us Press, © 2002. All rights

reserved. Used with permission.

Jeanne

Kun is President of Bethany

Association and a senior woman

leader in the Word

of

Life Community, Ann Arbor, Michigan,

USA. |

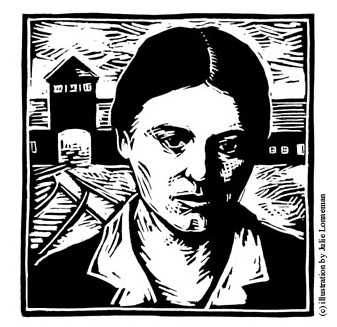

Blessed

by the Cross

The

Heroic

Life of Edith Stein

in Nazi Germany

A

Biographical reflection by Jeanne Kun

A

young woman in search of

the truth

“I keep

having to think of Queen Esther who

was taken from among her people

precisely that she might represent

them before the king,” Sister Teresa

Benedicta wrote to an Ursuline

religious sister late in 1938. “I am

a very poor and powerless little

Esther, but the King who chose me is

infinitely great and merciful. That

is such a great comfort.”

Edith

Stein was born into a

prominent Jewish family in Breslau,

Germany (present-day Wroclaw, Poland), on

Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement,

in 1891. As a teenager she abandoned

Judaism and became a

self-proclaimed atheist.

She

attended the university in Breslau and,

later, in Göttingen, where she sought

intellectual truth in the study of

philosophy and became a protégé of the

famed philosopher Edmund Husserl. She

earned her doctorate of philosophy in

1916, but her search for truth remained

unfulfilled.

The following year Edith

was impressed by the calm faith that

sustained a Christian friend at the

death of her husband. “It was my first

encounter with the cross and the divine

power that it bestows on those who carry

it,”

Edith later wrote. “For the

first time, I was seeing with my very

eyes the church, born from its

Redeemer’s sufferings, triumphant over

the sting of death. That was the moment

my unbelief collapsed and Christ shone

forth—in the mystery of the

cross.”

Taking

up the cross of Christ

Edith chose her religious name, Sister

Teresa Benedicta of the Cross,

anticipating that she would share in the

Lord’s sufferings. “By the cross I

understood the destiny of God’s people

which, even at that time, began to

announce itself,” she later explained to

a friend. “I thought that those who

recognized it as the cross of Christ had

to take it upon themselves in the name

of all.”

As the situation

worsened for Jews in Germany, Sister

Teresa Benedicta knew she was not safe

in the Cologne monastery and also

believed that her presence there put all

the nuns in danger. On the night of

December 31, 1938, she crossed into the

Netherlands where she was received at

the Carmel monastery in Echt. Her sister

Rosa, who had also become a Catholic,

later followed her and served as a lay

portress at the monastery. However, the

Nazis occupied the Netherlands in 1940

and Jews, even those who were converts

to Christianity, were no longer safe

there either.

A martyr through

the silent

working of divine grace

Sister Teresa Benedicta and Rosa were

arrested on August 2, 1942, as part of

Hitler’s orders to deport and liquidate

all non-Aryan Catholics. This was in

retaliation for a pastoral letter issued

by the Dutch bishops that protested Nazi

policies. As the two were taken from the

convent, Sr. Teresa was heard to say to

her sister: “Come, Rosa, let us go for

our people.” Their lives ended a week

later in the gas chamber at

Auschwitz.

Like Queen Esther, Edith

Stein identified with her fellow Jews in

their grave danger and interceded for

them. When she was formally declared

blessed in 1987 by the Catholic Church,

a selection from the Old Testament’s

Book of Esther was read at her

beatification ceremony.

When she was formally

declared a saint on October 11, 1998,

Pope John Paul II noted: “A young woman

in the search of the truth has become a

saint and martyr through the silent

working of divine grace: Teresa

Benedicta of the Cross, who from heaven

repeats to us today all the words that

marked her life: ‘Far be it from me to

glory except in the Cross of our Lord

Jesus Christ.’. . .

Now alongside Teresa of

Avila and Thérèse of Lisieux, another

Teresa takes her place among the hosts

of saints who do honor to the Carmelite

Order.”

Life

in a Jewish Family

From the writings of Edith

Stein

The highest of all the Jewish festivals is

the Day of Atonement, the day on

which the High Priest used to enter the

Holy of Holies to offer the sacrifice of

atonement for himself and for the people;

afterwards, the “scapegoat” upon whose

head, symbolically, the sins of all the

people had been laid was driven out into

the desert.

All

of this ritual has come to an end. But

even at present the day is observed with

prayer and fasting, and whoever preserves

but a trace of Judaism goes to the

“Temple” on this day.

Although

I

did not in any way scorn the delicacies

served on the other holidays, I was

especially attracted to the ritual of this

particular holy day when one refrained

from taking any food or drink for

twenty-four hours or more, and I loved it

more than any of the others. . .

For

me the day had an additional significance:

I was born on the Day of Atonement, and my

mother always considered it my real

birthday, although celebrations and gifts

were always forthcoming on October 12.

(She herself celebrated her birthday

according to the Jewish calendar, on the

Feast of Tabernacles; but she no longer

insisted on this custom for her children.)

She laid great stress on my being born on

the Day of Atonement, and I believe this

contributed more than anything else to her

youngest’s being especially dear to her.

[Excerpt from Edith

Stein’s autobiography, Life in a

Jewish Family, written in 1933,

translated by Josephine Koeppel, 1986]

|