“The

Father will give you another

Counselor”

–

John 14:16

The Holy

Spirit Reveals the Merciful Father.

.

by

Raniero Cantalamessa

1. A Year of the Lord's Mercy

Returning to his home in

Nazareth after his baptism in the Jordan,

Jesus solemnly applies the words of Isaiah

to himself:

“The Spirit of the Lord

is upon me,

because he has

anointed me to preach good news to the

poor.

He has sent me to

proclaim release to the captives

and recovering of

sight to the blind,

to set at liberty

those who are oppressed,

to proclaim the acceptable year of the

Lord.” (Luke 4:18-19)

It was thanks to the anointing of

the Holy Spirit that Jesus preached the good

news, healed the sick, comforted the afflicted,

and performed all his works of mercy. St. Basil

writes that the Holy Spirit was “inseparably

present” with Jesus so that his “every operation

was wrought with the co-operation of the

Spirit.”78 The Holy Spirit, who is

love personified in the Trinity, is also the

mercy of God personified. He is the very

“content” of divine mercy. Without the Holy

Spirit, “mercy” would be an empty word.

The name “Paraclete” clearly

indicates this. In announcing his coming,

Jesus says, “And I will pray the Father, and

he will give you another Counselor, to be with

you for ever” (John 14:16). “Another” here

implies “after having given me, Jesus, to

you.” The Holy Spirit is, therefore, the one

through whom the risen Jesus now continues his

work of “doing good and healing all” (Acts

10:38). The statement that the Paraclete “will

take what is mine and declare it to you” (John

16:14) also applies to mercy: the Holy Spirit

will open the treasures of Jesus’ mercy to

believers in every age. He will make Jesus’

mercy not just be remembered but also experienced.

The

Paraclete is active above all in the

sacrament of mercy, Confession. “He is the

remission of all sins,” says one of the

Church’s prayers.79 Because of

that, before giving absolution to a

penitent, a confessor says, “God, the

Father of mercies, through the death and

resurrection of his Son, has reconciled

the world to himself and sent the Holy

Spirit among us for the forgiveness of

sins; through the ministry of the Church

may God give you pardon and peace.”

Some

Church Fathers considered the oil the

Samaritan poured on the wounds of the man

who was robbed to be a symbol of the Holy

Spirit.80 A beautiful

African-American spiritual expresses this

thought with the evocative image of the

balm in Gilead: “There is a balm in

Gilead, / to heal the sin-sick soul

/. . . . / to make the

wounded whole.” Gilead is a place

mentioned in the Old Testament that was

famous for its perfumed healing ointment

(see Jeremiah 8:22). Listening to this

song we could almost imagine a street

vendor shouting out a list of his

merchandise and their prices. The whole

Church should be this “street vendor.” The balm the Church

offers today is no longer the medicinal

ointment of Gilead; it is the Holy

Spirit.

2. The Letter and the

Spirit, Justice and Mercy

The

Holy Spirit is the key to solving the very

tricky problem of the relationship between

the law and mercy. Commenting on Paul’s

saying that the letter kills but the Spirit

gives life (2 Corinthians 3:3-6), St. Thomas

Aquinas writes, “The ‘letter’ refers to

every written law that exists outside of

man, including the moral precepts of the

gospel. The ‘letter’ of the gospel, even of

its precepts, also kills without the inward

presence of the grace of faith that heals

us.”81 Shortly before that

statement, the holy doctor explains what he

means by “the grace of faith”: “The new law is primarily the

same grace of the Holy Spirit that is given

to believers.”82

This is

a bold assertion that none of us would dare

make if it did not come from two very great

doctors of the Latin Church, Augustine and

Thomas Aquinas. It finds confirmation

earlier in the very words of Christ and the

experience of the apostles. If a

proclamation of the beatitudes and the moral

teachings of the gospel were enough for us

to have eternal life, then there would have

been no need for Jesus to die and be raised

for us to receive the gift of the Spirit.

That is why he tells the apostles it is good

for him to go away so that he can send the

Paraclete upon them (see John 16:7). Look at

the experience of the apostles: they had

listened to all the precepts of the very

author of the gospel, but they were not able

to put them into practice until the Holy

Spirit came down upon them at Pentecost.

The conclusion that

emerges from all this is clear: if even the

gospel precepts without the Holy Spirit

would be “the letter that kills,” what can

we say about ecclesiastical laws, monastic

rules, and the canons in the canon law,

including those that regulate marriage? The

Spirit does not abolish or bypass the law;83

he does,

however, teach at what point the law should

move aside and yield to mercy. Obviously,

not every “letter” kills but only the one

that claims, all by itself and once and for

all, to regulate life or even substitute

itself for life.

3.

The Holy Spirit Reveals the Merciful

Father

An

essential work of the Holy Spirit with

respect to mercy is also that of changing

the picture people have in their minds of

God after they sin. One of the

causes—perhaps the main one—for the

alienation of people today from religion and

faith is the distorted image they have of

God. It is also the cause of a lifeless

Christianity that has no enthusiasm or joy

and is lived out more as a duty than as a

gift, by constraint rather than by

attraction.

What is this

“preconceived” idea of God in the collective

human unconscious that operates

automatically (in computer language, we

would say “by default”)? To find that out,

we only need to ask this question: “What

ideas, what words, what feelings

spontaneously arise for you before you think

about it when you come to the words in the

Lord’s Prayer ‘May your will be done’”? In

general, people say it with their heads bent

down in resignation inwardly, as if

preparing themselves for the worst.

People

unconsciously link God’s will to everything

that is unpleasant and painful, to what in

one way or another is seen as destroying

individual freedom and development. It is as

though God were the enemy of every

celebration, joy, and pleasure. People do

not take into account that in the New

Testament, the will of God is called “eudokia”

(see Ephesians 1:9; Luke 2:14), meaning,

“goodwill, kindness.” When we pray, “May

your will be done,” it is really like

saying, “Fulfill in me, Father, your plan of

love.” Mary said her fiat with that

attitude, and so did Jesus.

God is

generally seen as the Supreme Being, the

Omnipotent One, the Lord of time and

history, as an entity who asserts his power

over an individual from the outside. No

detail of human life escapes him. The

transgression of the law, disobedience to

the divine will, inexorably introduces a

disorder into the order willed by God from

all eternity. As a consequence, his infinite

justice requires reparation: a person will

need to do something for God so as to

reestablish the order that was disturbed in

creation, and this reparation will involve a

deprivation, a sacrifice. However, since

people are never able to be certain that the

“satisfaction” is enough, anxiety arises

over facing death and judgment. God is a

taskmaster who requires being paid back in

full!

Of

course, these people do not leave out the

mercy of God! But for them, mercy functions

only to moderate the necessary rigors of

justice. It rectifies the situation, but it

is an exception, not the rule. In practice,

then, they believe God’s love and

forgiveness depend on the love and

forgiveness they have for others: if you

forgive whoever offended you, God will be

able in turn to forgive you. It leads

to a relationship of

bargaining with God. Isn’t it true that

people think they need to accumulate merits

to get into heaven? And don’t people

attribute great significance to their

efforts—to the Masses they attend, to the

candles they light, and to the novenas they

make?

Since all these practices

have allowed so many people in the past to

demonstrate their love to God, they cannot

be thrown out the window but need to be

respected. God makes his flowers bloom in

all climates and his saints in all seasons.

We cannot deny, however, that again there is

a risk here of falling into a utilitarian

religion of “do ut des,” “I give so

that you can give, so that I can receive.”

Behind all of this is the presupposition

that a relationship with God depends on

human beings. People unconsciously presume

to “pay God his price” (see Psalm 49:7);

they do not want to be debtors but creditors

to God.

Where

does this twisted idea of God come from? Let

us leave aside individual and incidental

factors like a bad relationship with one’s

earthly father, which, in some cases, puts a

strain on the relationship with God the

Father. The basic reason for this terrible

“preconception” about God clearly appears

from what we have just said: the law, the

commandments. As long as people live under

the reign of sin, under the law, God seems

to be a severe Master, someone who is

opposed to the fulfillment of a person’s

earthly desires with his mandates of “You

should . . . You should

not” that comprise the commandments: “You

should not covet other’s goods, others’

spouses,” and so on. In this situation,

carnal human beings store up bitterness

against God deep in their hearts. They see

him as an adversary to their happiness, and

if it depended on them, they would be very

happy if God did not exist.84

The

first thing the Holy Spirit does when he

comes to dwell in us is to reveal a

different face of God to us. He shows him to

us as an ally, as a friend, as the one who

“did not spare his own Son but gave him up

for us all” (Romans 8:32). In brief, the

Holy Spirit shows us a very tender Father

who has given us the law not to stifle our

freedom but to protect it. A filial

sentiment then arises that makes us

spontaneously cry, “Abba, Father.” It

is like saying, “I did not know you, or I

knew you

only from hearing about you. Now I know you,

I know who you are, and I know that you

truly wish good for me and that you look

upon me with favor!” A son or daughter has

now replaced a servant; love has replaced

fear. This is what happens on the subjective

and existential level when a person is “born

anew of the Spirit” (see John 3:5, 7-8).

In

addition to the law, there has been another

reason in recent times for resentment

against God: human suffering, and especially

the suffering of the innocent. A nonbeliever

has written that human suffering “is the

rock of atheism.”85 The dilemma

is that either God can overcome evil but

does not want to, so he is not a father; or

that he wants to overcome evil but he

cannot, so he is not omnipotent. This is a

very old objection, but it has become

deafening in the wake of the tragedies of

World War II. “No one can believe in a God

as Father after Auschwitz,” someone has

written.

I

attempted to explain in the first chapter

the answer the Holy Spirit has given the

Church about this problem, which is that God

suffers alongside people. He is not

a far-off God who looks with indifference

at a person suffering on earth. To the

objection above, one can thus respond that

God can overcome evil but does not choose

to do it (at least in a general or normal

way) so as not to remove people’s free

will. God wants to overcome evil—and he

will—but with a new kind of victory, the

victory of love in which he takes evil

upon himself and converts it to good for

all eternity. It would be a magnificent

fruit of the Year of Mercy if it served to

restore the true picture of God that Jesus

came to earth to reveal to us.

4. Making Ourselves

Paracletes

The title “Paraclete”

not only speaks about God’s mercy toward

us but also opens for us a whole new field

of acts of mercy for one another. We need,

in other words, to become paracletes

ourselves! If it is true that the

Christian needs to be an alter

Christus, “another Christ,” it is just as

true that he or she needs to become “another

paraclete.”

The love of God has been

poured into our hearts through the Holy

Spirit (see Romans 5:5), whether it be the

love with which God loves us or the love

that has made us in turn capable of loving

God and our neighbor. When applied to

mercy—which is the form love takes in the

face of the suffering and sin of a person

who is loved—the following saying from the

apostle tells us something very important:

the Paraclete not only comforts us; he also

comes to comfort others and makes us able to

comfort them and be merciful. St. Paul

writes, “Blessed be the God and Father of

our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of mercies

and God of all comfort, who comforts

us in all our affliction, so that we may be

able to comfort those who are in any

affliction, with the comfort with

which we ourselves are comforted by

God [italics added]” (2 Corinthians 1:3-4).

The Greek word from which “Paraclete” is

derived appears five times in this text,

sometimes as a verb and sometimes as a noun.

It contains the essential elements for a

theology of consolation.

Consolation comes from God who is “the

Father of all comfort”; he comes to whoever

is afflicted. But he does not stop with that

person; his ultimate goal is reached when

those who have experienced consolation use

that experience in turn to comfort others.

But

console how? This is the important point.

With the very consolation with which we have

been consoled by God—a divine, not human,

consolation. That does not happen when we

are content to repeat empty words about

circumstances that leave things the way we

found them: “Don’t worry; don’t get upset;

you’ll see that everything will turn out for

the best!” We need instead to communicate

authentic consolation, which comes from “the

encouragement of the scriptures [so that] we

might have hope” (Romans 15:4). This also

explains the miracles that a simple word or

gesture in an atmosphere of prayer can

accomplish at the bedside of a sick person.

God is giving comfort through you.

In a

certain sense, the Holy Spirit needs us in

order for him to be the “Paraclete.” He

wants to comfort, defend, and exhort, but he

has no mouth, hands, or eyes to “embody” his

consolation. Or better, he has our hands,

our eyes, our mouths. Just as our soul acts,

moves, and smiles through the members of our

body, so the Holy Spirit does the same

through the members of “his” body, the

Church and us. St. Paul recommends to the

early Christians, “Therefore encourage one

another” (1 Thessalonians 5:11); translated

literally the verb here means “make

yourselves paracletes for one another.” If

the consolation and the mercy we receive

from the Spirit do not flow from us to

others, if we selfishly want to keep it for

ourselves, then very soon it stagnates.

Let us

ask for grace from Mary, whom Christian

devotion honors with two titles that

together signify “paraclete”: “Consoler

of the Afflicted” and “Advocate for

Sinners.” She has certainly made herself a

“paraclete” for us! A text from the Second

Vatican Council says, “The Mother of Jesus

shine[s] forth on earth, until the day of

the Lord shall come (cf. 2 Peter 3:10), as a

sign of sure hope and solace to the people

of God during its sojourn on earth.”86

Notes

78

St. Basil, On the Holy Spirit, XVI,

39, in Letters and Select Works,

trans. Blomfield Jackson, vol. 8, Nicene

and Post-Nicene Fathers (repr., Grand

Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1996), p. 25; see PG

32, p. 140.

79

Roman Missal, Tuesday after Pentecost.

80

Origen, Homilies on Luke, 34, trans.

Joseph T. Lienhard, vol. 94, Fathers of the

Church (Washington, DC: Catholic University

of America Press, 1996), pp. 139-140; see

SCh 87, p. 401.

81

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologiae,

I–IIae, q. 106, a. 2.

82

Ibid., q. 106, a. 1; see also St. Augustine,

The Spirit and the Letter, 21, 36,

pp. 221–222.

83

St. Augustine, The Spirit and the

Letter, 19, 34: “The law was given

that grace might be sought; grace was given

that the law might be fulfilled” (p. 220).

84

See Martin Luther, “Sermon for Pentecost,” The

Sermons of Martin Luther, vol. 3

(Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book, 2000), pp.

273–287.

85 The phrase comes from a

1835 drama by the nineteenth-century German

author Georg Büchner, Danton’s Death

[Dantons Tod], trans. Howard Brenton

and Jane Margaret Fry (London: Methuen,

1982), p. 43. In Act 3, a character asks,

“Why do I suffer? That is the rock of

atheism.”

86 Lumen gentium,

n. 68

Excerpt from The Gaze

of Mercy: A Commentary on Divine and Human

Mercy, © 2015 Raniero Cantalamessa,

published by The Word Among Us Press. Used

with permission.

|

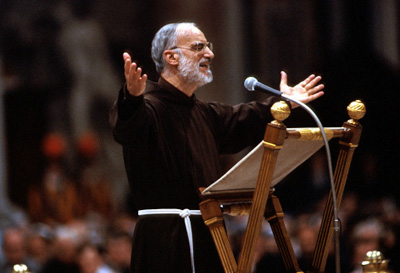

Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa,

O.F.M. Cap. (born July 22, 1934) is an

Italian Catholic priest in the Order

of Friars Minor Capuchin. He has

devoted his ministry to preaching and

writing. He is a Scripture scholar,

theologian, and noted author of

numerous books. Since 1980 he has

served as the Preacher to the Papal

Household under Pope John Paul II,

Pope Benedict XVI, and Pope Francis.

He is a noted ecumenist and frequent

worldwide speaker, and a member of the

Catholic Delegation for the Dialogue

with the Pentecostal Churches.

|

.l |