Losing Justin on Miscarriage as God's Bitter Word God made man in such a way that, if he simply did what was pleasant to him, he would in short order have a bunch of smaller clones of himself toddling around at his feet. And as this is what a man (or a woman) was made for, the man without children ought to ask himself: What good is everything I manage to build, if I can offer it to no one? To be sure, the parent’s calling is to give of himself, to the point of death, to meet the needs of his children. But the father (or mother) may find joy in this sacrifice, while the man or woman who is free of children all too often finds that his freedom is a burden, a loss, and a source of pain. Particular Losses

The reaction of several acquaintances to our loss was this: We were not taking this “complication” (as some put it) very well. And that word – complication – tells me something about the way we think of babies. The worldview goes something like this: Either a couple wants a baby, or they don’t. If they want a baby, miscarriage hurts them, but if they have another pregnancy, and are able to carry that baby to term, they will be perfectly happy. What many people do not fathom is that, to the father and mother, each particular child is a unique gift, and they desire to know this one individual who has left them. When a “miscarriage” occurs, the Christian family does not weep because the child is dead forever, for in fact the child lives. No, the family weeps for its personal loss – not the generic selfish loss of a child, but the particular selfish loss of this child. My wife and I would have been, in a worldly sense, better off without that baby. Our finances would have been more stable; our marriage would have had more time to establish itself; my wife would have been able to work full-time in her first year as a nurse. There was no external benefit to having that child, and the pregnancy was at least as worrying as it was exciting. And yet, losing that child was hard, one of the hardest things we have ever experienced. People were encouraging, but many did not seem to comprehend that this was not a matter of struggling with a lack of children in a generic way, but with the loss of this one irrevocably irreplaceable child. We heard whispers from the Lord about our baby. Perhaps it is presumptuous to say that. I just know that we were listening for God, and certain things came to us. We felt that this was a son, and we felt that the Lord was speaking to us about justice. In response to these senses, we named him Justin: Justin Benedict (the good word of justice). And yet, God’s “benediction” upon us did not seem either good or just at the time. It kept us from knowing our son, from watching him grow. It was a bitter word, a word that inspired anger and frustration. Blessings like these have the power to destroy, to diminish, to disillusion. Mourning and Questioning

When a man’s life does not come to fruition on earth, is it any less life? We hold mournful vigils for the losses of strangers while we “grin and bear” our own loss of a child born too soon. Perhaps if Christians responded to miscarriage with more hurt and anger, our response might signal to the secular world that we really do mean what we say about abortion. Holy sorrow is a virtue; that is, a way of responding to the reality of our lives in holiness. Lest we forget, it is our duty to mourn. The victims of miscarriage (by which term I indicate the parents, not the child) are bound to struggle with the concept of justice, as we did, and the Lord’s answers are not quick in coming. Is it for my sin that God has taken back his gift? Are we being punished, even as our son walks before the throne of God? In a sense, the answer is yes. It is for my sin that my son dies, as it was for Adam’s sin that Abel died, for David’s sin that Absalom died. We are being punished for our failings—that is the scriptural meaning of death. But punishment is not the meaning of miscarriage. Or, at least, punishment cannot whitewash all the perceived injustices of miscarriage – as it does not tend to satisfy as a simple explanation for cancer or for natural disaster, either. For here is the crux of the Old Testament, epitomized in the book of Job: For shame, I am not worthy of God’s blessing, but how much less worthy are some people that are being blessed! Why do the wicked prosper? How long must we wait for justice? These are questions that most people avoid. They avoid the questions by pretending that a miscarriage is “no big deal,” as if an eternal human life were not involved. They avoid the questions by distracting themselves, shifting their focus onto the next child, the next job, the next goal. They avoid the questions by opening themselves to sin, replacing a heart of flesh with a heart of stone – in short, becoming the wicked men that they despise. There are many ways to avoid the questions. But each way trades death for death. I can live by encountering death, or I can die by avoiding it; there is no middle ground. He who suffers much and does not question God is not the wise man, but the fool. The experience of a miscarriage ought to bring us into conflict with God, for it is a place where his interests and our own seem to collide. There is something deep going on here, a relationship more binding than the chains of death, to which the Lord is calling us. That is, as long as we keep listening. Dominionless Death

Man’s life can have meaning – God-given, permanent meaning – despite death. This meaningfulness of the just man’s life, in the Hebrew tradition, has no need for an afterlife. And yet, with the coming of the Messiah, death is conquered a second time, opening the way to heaven. Now, death not only fails to destroy a man’s meaning, it also fails to destroy a man’s life. Death moves from the category of “terminal” to “transitional.” The fact that Christ did not destroy, but instead redeemed, our experience of death ought to give us pause. The human journey (even the journey of a saint) passes through death. Scripture tells us that “the day of death is better than the day of birth” (Eclesiastes 7:1) It seems wise, then, to take every opportunity to consider death, both as a temporary evil and as a potential conduit of God’s grace. There is richness in a life that comprehends death, if only incompletely. We can encounter life entirely on our own terms. We cannot encounter death on our own terms. Had my wife and I been able to meet our son, we might easily have claimed him as our own and left his Creator out of the picture. But when our encounter with Justin was delayed (in our faithless moments, we feared, delayed forever), we were forced into a new encounter: an encounter with God. There is a strong connection between suffering and worship. For all we hear of Job being a complainer, we ought to consider the very first words he speaks. Informed of a wealth of calamity, Scripture says, Job “fell to the ground and worshiped,” saying: “Naked I came from my mother’s womb,The meaning of miscarriage is a mystery, much like the meaning of death itself. The Christian response to miscarriage is not guilt, but neither is it acceptance, as such. It is mourning. And, yes, questioning God. God the Other

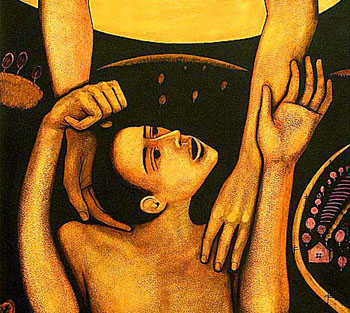

For the Father, we must remember, does not leave Job with empty hands. He shows up, and he proclaims his otherness: that he is eminent, that he is unapproachable. But in time, the Lord answers not only with eminence, but also with transcendence. For who else is Jesus but the “advocate” that Job has begged for, the “Redeemer” in whom Job places his trust? Job questions. Jacob wrestles with God. Rachel mourns. Jesus answers. The answer, in a word, is hope. Christians must remind themselves of this hope constantly. If the devil cannot make us lukewarm in our allegiance to Christ, he tries to make us hopeless. Love is the “greatest of these,” but hope is indispensable. A man can know all truth, and he can love with his whole being, but if he has no hope, all his virtue will be sabotaged by suffering. Suffering can lead either to hope (as in Romans 5) or to despair. If you have lost a child, perhaps you can see it more clearly in this image. He or she lives now in realms of glory, in harmony with Christ. I want you to imagine your child reading you the words of Jesus now, perhaps just whispering them in your ear: Most assuredly, I say to you that you will weep and lament, but the world will rejoice; and you will be sorrowful, but your sorrow will be turned into joy. A woman, when she is in labor, has sorrow because her hour has come; but as soon as she has given birth to the child, she no longer remembers the anguish, for joy that a human being has been born into the world. Therefore you now have sorrow; but I will see you again and your heart will rejoice, and your joy no one will take from you (John 16:20–22).God will be just to the victims of miscarriage. We just have to wait on him.

This article originally appeared in Touchstone Magazine, January/February 2007. Used with permission. Daniel Propson is an English

teacher at Lincoln High School in Ypsilanti, Michigan, USA. He and his

wife and are members of the Word

of Life Community. They live with their three young children in midtown

Detroit as part of a residential community outreach that provides mentoring,

training, and support for inner city youth to grow in Christian discipleship

and maturity.

|

. | |

|

copyright © 2009 The Sword of the Spirit | email: living.bulwark@yahoo.com publishing address: Park Royal Business Centre, 9-17 Park Royal Road, Suite 108, London NW10 7LQ, United Kingdom |

. |