February 2011 - Vol. 47.

.Countering the Deadly Vices with Godly Virtues: Part I “Make every effort to supplement your faith with virtue” (2 Peter 1:5) by Don Schwager Faith and virtue

Scripture makes clear that overcoming vice and acquiring virtue is essential for living as a man or woman of God. “Vice slays the wicked” (Psalm 34:21). “Pride goes before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall” (Proverbs 16:18). “Put to death therefore what is earthly in you: fornication, impurity, passion, evil desire, and covetousness, which is idolatry… Put on then, as God's chosen ones, holy and beloved, compassion, kindness, lowliness, meekness, and patience, forbearing one another and, if one has a complaint against another, forgiving each other; as the Lord has forgiven you, so you also must forgive. And above all these put on love, which binds everything together in perfect harmony” (Colossians 3:12-14). God created the human race in his image and likeness (Genesis 1:26-27). He created us to be men and women who think, act, and speak like himself. If we want to live as God intended us to as his sons and daughters, then we must conform our lives to his truth and submit our minds and hearts to his will (Romans 12:2). Only then can we truly grow as men and women of faith. The Apostle Peter explains that virtue is an essential building block for the ultimate quality in God’s kingdom: self-sacrificing love (agape). In his second letter, Peter presents a progression of qualities, virtues that builds towards this behavior that is like God – complete selflessness that frees us to love others without reserve. For this very reason make every effort to supplement your faith with virtue, and virtue with knowledge, and knowledge with self-control, and self-control with steadfastness, and steadfastness with godliness, and godliness with brotherly affection, and brotherly affection with love. For if these things are yours and abound, they keep you from being ineffective or unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. For whoever lacks these things is blind and shortsighted and has forgotten that he was cleansed from his old sins. Therefore, brethren, be the more zealous to confirm your call and election, for if you do this you will never fall; so there will be richly provided for you an entrance into the eternal kingdom of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. (2 Peter 1:5-11)Peter tells us that faith should lead to virtue and virtue to true knowledge and understanding of God and his word. Moral truth and moral goodness are rooted in God, who is the source of all that is good and true. If we want to bear fruit in our lives and live effectively as God intended, then we must root our minds and hearts in his word of truth. Why should we “make every effort to supplement our faith with virtue?” Peter explains the consequences for choosing for virtue: “They keep you from being ineffective or unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ,” and rather soberingly, without them we become “blind and short-sighted.” We want our children and we want ourselves to be effective and fruitful in Christ, and we want to be clear-sighted, not blind or short-sighted. Note also that acquiring virtue requires effort. Peter says, “Make every effort…” Acquiring virtue and growing in character is not just an optional extra for advancing one’s education and one’s training in skills and tasks. Individuals and societies grow or decline, thrive or collapse, depending on their moral strength and their determination to root out vice and to act with justice, prudence, fortitude, and temperance. The great Roman Empire, which lasted for centuries, is a well-known and sobering example. Historians say that it collapsed from moral decay even before the barbarians pillaged its cities. Given the importance of virtue, how do we acquire it? What lessons can we learn from Scripture and the wise sages throughout history? Acquiring virtue

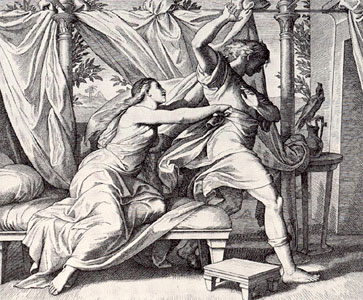

The idea of acquiring virtue by imitating the noble example of others was a simple but profound truth which was recognized in Greek and Roman antiquity. Seneca (1 BC-65AD), a Roman philosopher wrote: “Plato, Aristotle, and the whole throng of sages ...derived more benefit from the character than from the words of Socrates. The way is long if one follows precepts, but short and accommodating if one imitates examples.” Long before Seneca, Aristotle (384-322 BC), a Greek philosopher and student of Plato, taught: “We become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts.” Aristotle showed that the pursuit of virtue was indissolubly bound to deeds, and that good actions are not simply the end towards which one strives, but the means to reach the goal. A virtuous life is only possible through the repeated performance of good deeds. Plutarch (46-120 AD), an influential Greek philosopher, recognized that “a slight thing, like a phrase or a jest” often revealed more of character than “battles where thousands fall.” The philosophers and teachers of antiquity recognized that character often has more to do with constancy and steadiness than sheer displays of bravery or courage. In the Scriptures precepts are often buttressed by examples. Abraham is a model of faith in leaving his homeland in order to follow the call of the Lord and in his willing obedience when the Lord tested him to offer up his only son (Hebrews 11:8). Joseph is a model of patience and long-suffering as he endured murderous mistreatment by his brothers and slavery in Egypt (Genesis 37ff; Psalm 105:16-22). Deborah, a prophetess and judge in Israel, is noted for her wisdom and courage in defending her people (Judges 4,5). Esther is noted for her piety and courageous determination to save her people from destruction (Book of Esther). Ruth is a model of devoted love and faithfulness (Book of Ruth). Job is noted for his perseverance (steadfastness) in the face of calamity and testing (James 5:11). Joshua is a model of courage and determination in fighting through obstacles to achieve God's will. Elijah is a model of a righteous man who has power in prayer (James 5:17). The Letter to the Hebrews, chapter 11, gives a roster of men and women of faith, including some of the people mentioned above. It lists Abel, Enoch, Noah, Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, Rahab, Gideon, Barak, Samson, Jephthah, David, Samuel, and the prophets. "Go and do likewise"

Clement of Alexandria (150-215 AD), an early church teacher, wrote: “Our tutor, Jesus, exemplifies the true life and trains the one who is in Christ. He gives commands and embodies the commands, that we might be able to accomplish them.”Augustine (354-430 AD), who was a gifted teacher, writer, and bishop of Hippo in North Africa, identified all virtue with the person of Christ: Now we require many virtues, and from these virtues we advance to virtue itself. What virtue, you inquire? I reply: Christ, the very virtue and wisdom of God. He gives diverse virtues here below, and he will also supply the one virtue, namely himself, for all of the other virtues which are useful and necessary in this vale of tears.2Palladius (365-425 AD), a bishop in Egypt, wrote at the beginning of his Lausiac History: Words and syllables do not constitute teaching. ..Teaching consists of virtuous acts of conduct. ..This is how Jesus taught. ..He did not use fine language...he required the formation of character.Today's social condition We can't divorce a study on Christian character and the virtues from the social condition around us. Our secularist society extols freedom and autonomy apart from moral responsibility and character. This selfist society disdains virtuous living and holds character in disrepute. “Having character” is associated with being set in one's ways, inflexible, unbending, or obstinate. Character and the moral virtues are being undermined due to subjectivism and individualism. Moral standards and judgments are now measured by what individuals know or feel for themselves.3Freedom is defined as doing what is right for you and doing what works for you apart from any objective standards of morality. This “idea of an autonomous ethics, without religious or metaphysical foundation”4can be traced back to the Enlightenment thinkers who threw off the “fetters” of religious faith and moral tradition for the freedom to redefine moral ethics based on human reason alone. This secularist modem notion of freedom is a mask for what the scriptures call slavery to one's passions and folly. Charles Colson in his book. Against the Night, describes this kind of slavery: To be governed by nothing more than the free expression of one's passions can be the most terrifying repression of all. Like the young woman profiled some years ago in Psychology Today who told her psychiatrist that she was exhausted by her life style-an endless round of parties, sex, drugs, and alcohol. "Why don't you stop?" he asked her. Astonished, she got up abruptly. "You mean, I don't have to do what I want to do?"5As free agents in a secularist society, we are often faced with multiple choices and options. We find ourselves having to choose among numerous alternatives which the modern world presents to us. We can choose to live our lives by certain beliefs and intentions rather than others. Many choices involve questions about our intentions and beliefs, such as whether we will fulfill our obligations and sustain our commitments, whether we will cheat or not on our income tax, how we will find meaning in our work, and what we decide to do with our time and money. A person's capacity for self-determination is crucial if he or she is to have character.6 We do not have to be at the mercy of forces or events. We can grow in character if we choose to make the right kind of response to events which are often beyond our control. Character used to be talked about as something vital and important for the survival of the nation and the growth of the Christian church. Today hardly anyone says much about character or the moral virtues. They are largely ignored. But lack of character unfortunately does undermine individuals and society. Again Charles Colson writes: Societies are tragically vulnerable when the men and women who compose them lack character. A nation or a culture cannot endure for long unless it is undergirded by common values such as valor, public-spiritedness, respect for others and for the law; it cannot stand unless it is populated by people who will act on motives superior to their own immediate interest. Keeping the law, respecting human life and property, loving one's family, fighting to defend national goals, helping the unfortunate, paying taxes – all these depend on the individual virtues of courage, loyalty, charity, compassion, civility, and duty.7Meaning of character Character (that is, good character) implies moral goodness; but the goodness of an individual is not something which is automatic. It must be acquired and cultivated. Character is first the inner disposition to act in morally good ways as situations present themselves. Character has to do with how we actually live day in and day out, how we handle situations in life, and how we treat people. Character won't necessarily tell us how someone might feel or think in a given situation, but it will indicate how someone is disposed to act in a given situation, what he or she will likely do, how he or she will respond. If a person is disposed to be honest, then their honesty in dealing with financial matters is part of their character. Such a man or woman can be trusted with financial matters because they are a man or woman of honest character. The opposite of good character is bad character, that disposition to act in morally bad ways as situations present themselves."8 We use character to mark off what is distinctive in a person, what is in some measure deliberate, what one can decide to be as opposed to what one is naturally. Since one can chose to have character, we can surmise what he or she is likely to do, once we know what their character is. For example, some people are naturally and incurably slow, quiet, or shy, while others are talkative and outgoing, but each person, regardless of their personality traits or tendencies, can choose to be honest or deceitful, selfish or generous, kind or rude. One's inclinations and desires, which are part of their nature, can only enter into what we call a person's good character in so far as he or she chooses to satisfy them according to what is morally right and appropriate. Stanley Hauerwas, in his book, Character and the Christian Life, describes the formative role of character in defining one's identity and orientation to life: Nothing about my being is more “me” than my character. Character is the basic aspect of our existence. It is the mode of the formation of our “I,” for it is character that provides the content of that “I.”If we are to be changed in any fundamental sense, then it must be a change of character. Nothing is more nearly at the “heart” of who we are than our character. It is our character that determines the primary orientation and direction which we embody through our beliefs and actions.9 Having character

One's integrity of character can be measured by the strength of their most serious convictions, and by their determination and willingness to undergo harm and even death rather than to violate those convictions. Thomas More was such an individual, valuing his conscience more than his life. Robert Bolt, in his play, A Man for All Seasons, portrays the character of Sir Thomas More when he was put to the supreme test when Henry VIII required More to take an oath which he believed to be false. While More was imprisoned in the Tower, his family tried to persuade him to take the oath. Thomas replied to his daughter, Meg: "When a man takes an oath, Meg, he's holding his own self in his own hands. Like water (he cups his hands). And if he opens his fingers then – he needn't hope to find himself again."10 Bolt explains: ...why do I take as my hero a man who brings about his own death because he can't put his hand on an old black book and tell an ordinary lie? For this reason: A man takes an oath only when he wants to commit himself quite exceptionally to the statement, when he wants to make an identity between the truth of it and his own virtue; he offers himself as a guarantee. And it works. There is a special kind of shrug for a perjurer; we feel that the man has no self to commit, no guarantee to offer. ... But though few of us have anything in ourselves like an immortal soul which we regard as absolutely inviolable, yet most of us still feel something which we should prefer, on the whole, not to violate. Most men feel when they swear an oath (the marriage vow for example) that they have invested something.11At his execution, Thomas More, in compliance with the King's wishes, spoke but a few words that he died the King's good servant, but God's first. Two centuries later, Samuel Johnson wrote of More: “He was the person of the greatest virtue these islands ever produced.” Moral vision

Character in its purest form is most clearly exemplified in the example of one whose life is dominated by an all-consuming purpose or direction higher than oneself. Francis of Assisi gave up inherited wealth for a life of voluntary poverty in his single-hearted pursuit of the love of God. Mother Theresa's life of heroic service to unwanted and poverty-stricken children and to neglected, dying invalids of Calcutta was fueled by her all-consuming love for Jesus. We grow in character to the degree that we attain singleness of purpose and direction. If we discover that we have better chances of attaining a job promotion and career advancement by lowering our standards of truthfulness, honesty, integrity, and respect for others in our financial transactions, or if we discover that we can increase our earnings and grow in financial wealth by taking advantage of others, treating them unfairly or unjustly, then we must choose. If we compromise on what is the morally right and good thing to do, then we open the door to accepting morally bad ways of thinking and acting. We become what we have chosen. The kind of person we are, our character, determines to a large extent the kind of future we will face and live. Character is thus not an end in itself, but a means for achieving the purpose God created us for, namely to live godly lives that bring honor and glory to his name. Moral education

Moral education often makes use of moral tales and parables to instill moral principles. The survival of the Jewish people and their way of life would not be possible without the stories that gave meaning to Jewish moral tradition. One such story, taken from a collection of traditional Jewish tales, highlights the importance of example in moral education. There was once a rabbi in a small Jewish village in Russia who vanished every Friday morning for several hours. The devoted villagers boasted that during these hours their rabbi ascended to heaven to talk with God. A skeptical newcomer arrived in town, determined to discover where the rabbi really was.The story concludes that the newcomer stayed on in the village and became a disciple of the rabbi. And whenever he hears one of his fellow villagers say, “On Friday morning our rabbi ascends all the way to heaven,” the newcomer quietly adds, “If not higher.”13A community of virtuous people A person grows, for better or for worse, by imitating others, that is, by living the way others live. Christians are called to imitate Christ, to be like him, to possess the same character and virtues that Jesus Christ had. This is not something we can achieve by our own efforts, but by cooperating with God's grace. To be like Christ, to grow in Christlike virtues, requires that we become part of a community that practices Christian virtues. Christians need a community of a particular kind to live well morally. Since the Christian church is called to be a holy community, we need to be a people capable of being faithful to a way of life, even when that way of life is in conflict with what passes as "morality" in the larger society. Christians cannot be morally autonomous, but must be willing to belong to a community which is committed to worshipping God and to living a godly way of life. Christians are called to be a certain kind of people, a people of godly character who live virtuous lives, and who shine as lights in a darkened world, pointing the way to the kingdom of God. As Jesus says in his Sermon on the Mount: You are the light of the world. A city on a hill cannot be hidden. Neither do people light a lamp and put in under a bowl. Instead they put it on a stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house. In the same way, let your light shine before men, that they may see your good deeds and praise your Father in heaven. (Matthew 5:14-16) [Don Schwager is a member of The Servants of the Word and the author of the Daily Scripture Reading and Meditation website.] 1 For a fuller treatment on the pursuit of virtue by both early Christian and pagan teachers see the following: "The Lives of the Saints and the Pursuit of Virtue" by Robert L. Wilken, Professor of the History of Christianity at the University of Virginia, in First Things, (published by Religion and Public Life, New York, N.Y.) December, 1990, pp. 45-51. 2. Quote from Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (354-430), in Enarrationes in Psalmos 83, no. II. 3. Modem secularists redefine character, virtue and vice to suit their own humanistic belief system and world-view. The following example is taken from Eric Fromm, Man for Himself (New York: Rinehart, 1947), p. 17: "I shall attempt to show that the character structure of the mature and integrated personality, the productive character, constitutes the source and basis of 'virtue', and that 'vice', in the last analysis, is indifference to one's own self and self-mutilation. Not self-renunciation nor selfishness but the affirmation of his truly human self, are the supreme values of humanistic ethics. If man is to have confidence in values, he must know himself and the capacity of his nature for goodness and productiveness."4. Quote from Eric Voegel in, From Enlightenment to Revolution (ed. John H. Hallowell, Duke University Press, Durham, N.C., 1975), pg. 85. 5. Quote from Charles Colson, Against the Night: Living in the New Dark Ages (Servant Publications, Ann Arbor, MI, 1989), pg. 58. 6. The following excerpt is from Vision and Virtue: Essays in Christian Ethical Reflection, by Stanley Hauerwas, (Fides Publishers, Inc., Notre Dame, Indiana, 1974). "Character is not a mere public apearance that leaves a more fundamental self hidden; it is the very reality of who we are as self-determining agents. Our character is not determined by our particular society, environment, or psychological traits; these become part of our character, to be sure, but only as they are received and intepreted in the descriptions which we embody in our intentional action. Our character is our deliberate disposition to use a certain range of reasons for our actions rather than others (such a range is usually what is meant by moral vision), for it is by having reasons and forming our actions accordingly that our character is at once revealed and molded."7. Quote from Charles Colson, Against the Night: Living in the New Dark Ages (Servant Publications, Ann Arbor, MI, 1989), pg. 67. 8. Steve Clark has written an excellent treatment on character formation in the following article: "The Contemporary Ethos and the People It Molds", by Stephen B. Clark, in The Cutting Edge, pp. 51-59, (edited by Kevin Perrotta, published by The Alliance for Faith and Renewal, Ann Arbor, MI. 1991). 9. Quote from Stanley Hauerwas, Character and the Christian Life: A Study in Theological Ethics (Trinity University Press. 1975, pg. 203): 10. Quote taken from A Man For Alt Seasons, a play by Robert Bolt, pg. 81 (Scholastic Book Services, 1960, 1962, New York) 11. ibid., pgs. xii-xii 12. An excellent book on the role of parents in the character development of children: Character Building: a guide for parents and teachers, by David Isaacs (Four Courts Press, 1984, Dublin, Ireland) 13. This story is quoted by Christina Hoff Sommers, in an article entitled "Teaching the Virtues", pg. 4, November, 1991 issue of Imprimis, Vol. 20, No. 11, a publication of Hilisdale College, Hilisdale, Michigan.

|

. | |

|

publishing address: Park Royal Business Centre, 9-17 Park Royal Road, Suite 108, London NW10 7LQ, United Kingdom email: living.bulwark@yahoo.com |

. |