February

2010

- Vol. 37

.

Witnesses

in the Jungle

Jim

Elliot, Nate Saint, & Fellow

Missionaries

by

Jeanne Kun

In January 1956 the world was shocked to hear

that a primitive tribe in the rain forest of

Ecuador had killed five American missionaries.

Jim Elliot, Nate Saint, Ed McCully, Pete

Fleming, and Roger Youderian had been working

at various jungle mission stations among the

Quichua and Jivaro Indians for several years.

The men, Protestant missionaries in their

twenties and thirties, had been accompanied by

their wives. Each couple was eager to share

the message of the gospel with those who had

never heard it. But, above all, they were

dedicated to the Lord himself and sought to be

obedient to him in all things.

Ed

McCully, Pete Fleming, and Jim Elliot

Jim Elliot and his friends had hoped and

prayed to be able to make contact with an

isolated and hostile people known by other

tribes as the Aucas (“savages” in Quichua)

because of their fierce infighting and hatred

for outsiders. With his skill as a pilot for

the Missionary Aviation Fellowship, Nate Saint

had made it possible for the men to fly over

the Auca settlements deep into the jungle and

drop such gifts as cloth, axes, and cooking

pots to assure them that their intentions were

friendly and to win their trust. The Aucas

reciprocated, tying native gifts – a

parrot, a headband of woven feathers, manioc,

and bananas – onto the plane’s

drop-line.

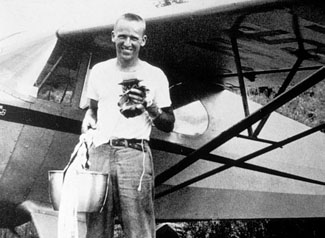

Nate

Saint next to his plane with camping

gear

When the mission team landed on the banks of

the Curaray River a few miles from the Auca

village and set up camp, their hopes were

rewarded: Three Aucas came out of the jungle

and spent the day at the camp trying to

communicate with the men, delightedly taking a

ride in the plane, and curiously inspecting

the missionaries’ equipment.

Two days later, on January 8, 1956, as Nate

flew over the camp, he saw a group of Aucas

headed toward it through the jungle. He landed

near the campsite on the river bank, shouted

the news “They’re on their way!” to Jim,

Roger, Pete, and Ed, and by radio notified

Marj Saint at the mission base of the

hoped-for meeting. The next designated radio

contact with their wives was never made.

widows

listen to the report of their husbands

fate

The following morning, one of Nate’s

co-workers from the Missionary Aviation

Fellowship flew over the site in search of the

men and located the plane. All of its fabric

had been stripped. Later a body was sighted,

floating face down in the river, and then

another. An armed expedition made up of the

missionaries’ colleagues, military personnel,

and Quichuas set off on foot, hoping to find

the other men still alive somewhere in the

rain forest. A few days later, the other

bodies, speared and sprawled in the sand and

muddy river water, were discovered by

helicopter. The ground party recovered four of

the bodies and buried them on the banks of the

Curaray. The body of the fifth missionary had

been identified earlier by an advance party of

Quichuas, but was washed away in a

storm.

In the preface of Shadow of the Almighty:

The Life and Testament of Jim Elliot,

first published in 1958, Elisabeth Elliot

wrote:

| “Jim’s aim was to know God. His

course, obedience – the only

course that could lead to the

fulfillment of his aim. His end was

what some would call an extraordinary

death, although in facing death he had

quietly pointed out that many have

died because of obedience to God. He

and the other men with whom he died

were hailed as heroes, ‘martyrs.’ I do

no approve. Nor would they have

approved.

“Is the distinction between living

for Christ and dying for him, after

all, so great? Is not the second the

logical conclusion of the first?

Furthermore, to live for God is to

die, ‘daily,’ as the apostle Paul

put it. It is to lose everything

that we may gain Christ. It is in

thus laying down our lives that we

find them.

“Those who want to know him

[Christ] must walk the same path

with him. These are the ‘martyrs’ in

the scriptural sense of the word,

which means simply ‘witnesses.’ In

life, as well as in death, we are

called to be ‘witnesses’ – to

‘bear the stamp of Christ.’

“I believe that Jim Elliot was one

of these. His letters and journals

are the tangible ground for my

belief. They are not mine to

withhold. They are a part of the

human story, the story of a man in

his relations to the Almighty. They

are facts.”

|

Less than three years after the five men’s

deaths, Elisabeth Elliot and Rachel Saint,

Nate’s sister, made contact with the Aucas – who in

their own language called themselves Huaorani or

“the people” –

through the help of an Huaorani woman who

had earlier fled from her tribe. The Huaorani

accepted the two women and Elisabeth’s daughter

to live among them because they wondered why the

missionaries had let themselves be killed rather

than shoot any of their attackers. Then they

heard the full story of how the men had come to

tell them of Jesus, who “freely allowed his own

death to benefit all people.

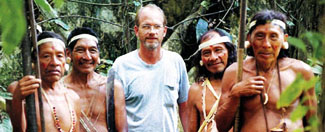

Steve

Saint continues to visit the tribe

regularly

Rachel spent more than thirty years working

among the Huaorani. Steve, Nate Saint’s son,

often visited his Aunt Rachel and grew up

knowing the men who learned to “walk on God’s

trail” after they had killed his father.

In an unbelievable expression of

reconciliation, Steve Saint, Nate’s son, was

baptized by two of the men who murdered his

father, in the very river where his father

died. Steve Saint has worked as a missionary

in West Africa, Central America and South

America.

At the request of the Waodani elders, he

returned to the Amazon in 1995 along with his

wife and children to live among the tribe for

several months. While working with the

Huaorani to build an airstrip in the jungle,

Steve Saint spoke with Gikita, the leader of

the attack. Then eighty years old, Gikita was

eager to “go to heaven and live peacefully

with the five men who came to tell him about

Wangongi, creator God.”

Jeanne

Kun is a noted author and a senior womens'

leader in the Word

of

Life Community, Ann Arbor, Michigan,

USA.

This

article is excerpted from the book, Even Unto

Death: Wisdom from Modern Martyrs,

edited by Jeanne Kun, The Word Among

Us Press, © 2002. All rights reserved.

Used with permission. The book can be

ordered from WAU

Press.

Recommended

reading:

Shadow

of

the Almighty: The Life and Testament of

Jim Elliot, by Elisabeth Elliot, 1958

End

of the Spear, by Steve Saint, Tyndale

House Publishers (15 May 2006)

Recommended

viewing:

Testimony by Steve

Saint, End of the Spear,

YouTube video

Beyond

the

Gates of Splendor, story of Jim

Elliot and missionary companions, YouTube

video

|

team on

the banks of the Curaray River

From Jim

Elliot’s journal:

He is no

fool who gives what he cannot keep to

gain what he cannot lose. (1949)

God, I

pray Thee, light these sticks of my life

and may I burn for Thee. Consume my

life, my God, for it is Thine. I seek

not a long life, but a full one, like

you, Lord Jesus. (1948)

Father,

take my life, yea, my blood if Thou

wilt, and consume it with Thine

enveloping fire. I would not save it,

for it is not mine to save. Have it

Lord, have it all. Pour out my life as

an oblation for the world. Blood is only

of value as it flows before Thine altar.

(1948)

Gave

myself for Auca work more definitely

than ever, asking for spiritual valor,

plain and miraculous guidance. . . .”

(May 1952)

Jim Elliot

in the Curaray River surveys the jungle

A hymn

written by Jim Elliot in Quichua,

describing what happens when a man

dies, using a simile from Ecclesiastes

11:3 which was simple and

understandable to the Indians:

“If a man

dies, he falls like a tree.

Wherever

he falls, there he lies.

If he is

not a believer, he goes to the

fire-lake.

“But on

the other hand, a believer,

If death

overtakes him,

Will not

fall, rather will rise

That very

moment, to God’s house.”

Nate

Saint’s description of his work serving

pioneering missionaries through

aviation:

Their call

of God is to the region beyond the ends

of civilization’s roads—where there is

no other form of transportation. They

have probed the frontiers to the limit

of physical capacity and prayed for a

means of reaching regions beyond—a land

of witch doctors and evil spirits—a land

where the woman has no soul; she’s just

a beast of burden—a land where there’s

no word for love in their vocabulary—no

word to express the love of a father for

his son. In order to reach these people

for whom Christ died, pioneer

missionaries slug it out on the jungle

trails day after day, sometimes for

weeks, often in mud up to their knees,

while up above them the towering

tropical trees push upward in a

never-ending struggle for light.

It is our

task to lift these missionaries up off

those rigorous, life-consuming, and

morale-breaking jungle trails—lift them

up to where five minutes in a plane

equals twenty-four hours on foot. The

reason for all this is not a matter of

bringing comfort to the missionaries.

They don’t go to the steaming, tropical

jungles looking for comfort in the first

place. It’s a matter of gaining precious

time, of redeeming days and weeks,

months and even years that can be spent

in giving the Word of Life to primitive

people.

May the

time never come when mankind no longer

hears the soft footsteps of the herald

angel, or his cheering words that

penetrate the soul. Should such a time

come all will be lost. Then indeed we

shall be living in bankruptcy and hope

will die in our hearts.

Nate

Saint’s description of the first gift

drop made to the Aucas:

We

continued circling until the gift was

drifting in a small lazy circle below

us, ribbons fluttering nicely. Finally

the gift appeared to be pretty close to

the trees below. Once I believe the

ribbons dragged across a tree and hung

up momentarily. We held our breath while

the kettle lowered toward the earth. It

hit about two or three feet from the

water directly in line with the path to

the house. Finally the line was free and

there was our messenger of good will,

love and faith two thousand feet below

on the sandbar. In a sense we had

delivered the first gospel message by

sign language to a people who are a

quarter of a mile away vertically . . .

fifty miles away horizontally . . . and

continents and wide seas away

psychologically.

From Jim

Elliot’s last letter to his parents,

written on December 28, 1955:

By the

time this reaches you, Ed [McCully] and

Pete [Fleming] and I and another fellow

[Roger Youderian] will have attempted

with Nate a contact with the Aucas. We

have prayed for this and prepared for

several months, keeping the whole thing

secret (not even our nearby missionary

friends know of it yet). Some time ago

on survey flights Nate located two

groups of their houses, and ever since

that time we have made weekly friendship

flights, dropping gifts and shouting

phrases from a loud speaker in their

language, which we got from a woman in

Ila. Nate has used his drop-cord system

to land things right at their doorstep

and we have received several gifts back

from them, pets and food and things they

make tied onto this cord. Our plan is to

go downriver and land on a beach we have

surveyed not far from their place, build

a tree house which I have prefabricated

with our power-saw here, then invite

them over by calling to them from the

plane. The contact is planned for Friday

or Saturday, January 6 or 7. We may have

to wait longer. I don’t have to remind

you that these are completely naked

savages (I saw the first sign of clothes

last week—a G-string), who have never

had any contact with white men other

than killing. They do not have fire

except what they make from rubbing

sticks together on moss. They use bark

cloth for carrying their babies, sleep

in hammocks, steal machetes and axes

when they kill our Indians. They have no

word for God in their language, only for

devils and spirits. I know you will

pray. Our orders are “the gospel to

every creature.”

—Your

loving

son and brother, Jim

From a

letter written by Elisabeth Elliot to

her parents on January 11, 1956, while

the five wives were waiting for news of

the fate of their husbands:

I want you

to know that your prayers are being

answered moment by moment as regards

me—I am ever so conscious of the

everlasting arms. As yet we know only

that two bodies have been sighted from

the air but not identified.

Jim was

confident, as was I, of God’s leading.

There are no regrets.

Nothing

was more burning in his heart than that

Christ should be named among the Aucas.

By life or death, oh, may God get glory

to himself.

Pray that

whatever the outcome I may learn the

lessons needful. I want to serve the

Lord in the future, so pray for his

continued grace and guidance. I have no

idea what I will do if Jim is dead, but

the Lord knows and I am at rest.

We hope

for final word tomorrow and trust our

loving Father who never wastes anything.

All my love,

Betty

Selection of

quotes from

Shadow of

the Almighty: The Life and Testament of

Jim Elliot, by Elizabeth Elliot.

Copyright 1985 by Elizabeth Elliot

(HarperCollins Publishers Inc.)

Jungle

Pilot: The Life and Witness of Nate

Saint, by Russel T. Hitt.

Copyright 1959 by The Fields, Inc.

(HarperCollins Publishers Inc)

|