A Grace-less Community by Jon Wilson In our age of individualism and fragmentation, community has become something of a buzz-word. People yearn for connection, relationships, and authenticity, and they have a sense that community is the thing that is missing from their lives. For some, however, community is a lived reality. I have known community all my life, from the tight-knit Dutch Reformed community of my youth to the intentional Christian community of which I am now a part. With this experience comes the understanding that community has its own attendant pitfalls and dangers, whether pressure to conform, the need to keep up appearances, or the temptation to hide problems and weaknesses. These hazards are narrated with pitiless clarity in Alan Paton’s novel, Too Late the Phalarope. Paton, a South African author and political activist, wrote in the middle decades of the 20th century, addressing the racial and social injustices of the South African culture of his day. The novel tells the story of Pieter van Vlaanderen, a military hero, rugby star, and police lieutenant who becomes sexually involved with a poor black woman of his town. His crime is discovered, he goes to jail, and his family is torn apart. While the cover art and editorial blurb of the current edition of the book seem to want to bill the story as one of forbidden love and courageous taboo-breaking, these “themes that sell” have no place in this book. Rather, Paton weaves a complex tale of a man, and indeed, a family searching for spiritual peace in the midst of a flawed Christian culture which has the potential to free, but in the end brings brokenness and bondage. Pieter van Vlaanderen was an unusual child, alternating between the hardy athlete and the sensitive aesthete. His harsh father saw in him a girl who picked flowers; his chastening would bring on a fit of boyish temper as Pieter would respond with some feat of physical prowess. While he grew to become venerated as a rugby star, he also became a man haunted by something unnamed, unseen except by those closest to him. Pieter’s Aunt Sophie, the story’s narrator, brings the insight of hindsight to the telling of the tale, and we are shown the deep ambivalence of Pieter’s relationship to his father. They both love, almost idolize, one another, but their encounters too often end in anger and misunderstanding. The father is unable to express love and acceptance of the boy, and this inability is passed on to and internalized by the son. Aunt Sophie also explains the inadequacies of Pieter’s marriage and sexual relationship with his wife, Nellie. They love one another, but Nellie is also afraid of Pieter, afraid that there is something unknown about him that can harm her. Aunt Sophie’s theory is that a more true and whole giving of herself to her husband would have prevented the ultimate harm which he did inflict on her. When Pieter comes under the spell of the “mad sickness,” his name for the lust he struggles with, he is finally left without the defense that would have been his as a happily married man.

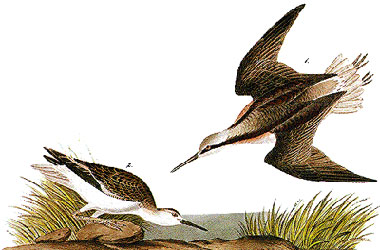

Pharlarope by Alexander Wilson But in the end, Pieter is lost through lack of grace, the grace he should have known as a member of his community. This is the true heartbreak of the novel, the missed opportunities for grace. The many times that Pieter does not speak of his troubles to sympathetic friends. The love and warmth of his marriage that turns cold and bitter all too quickly, all too often. The powerful sermon about the mercy of God, about our need for grace, a sermon finally left unheeded. And most poignant of all, the father and son together sighting the phalarope, the bird they had spoken of, argued about; a moment of connection, of grace, that came too late to save the son from himself. Paton’s novel has a strong sense of place. His lyricism fills the reader with longing for a land of such beauty as South Africa. His affectionate portrayal of the Dutch Reformed community brought me with a smile back to my own upbringing. Yet in writing about a land fractured by injustice, he avoids the temptation to produce a political tract. Rather, he tells of a human, even a spiritual tragedy. His narrative puts flesh on abstract, theological concepts like original sin, human frailty, forgiveness, and grace. He reminds us that community is not enough. For community to be life-giving, it has to be community awash in love, vulnerability, and humility; it has to be awash in grace. [Jon Wilson is a coordinator

of Word of Life, a member

community of the Sword of the Spirit. He and his wife, Melody and their

four children live in Ypsilanti, Michigan, USA.]

|

. | |||

|

publishing address: Park Royal Business Centre, 9-17 Park Royal Road, Suite 108, London NW10 7LQ, United Kingdom email: living.bulwark@yahoo.com |

. |