|

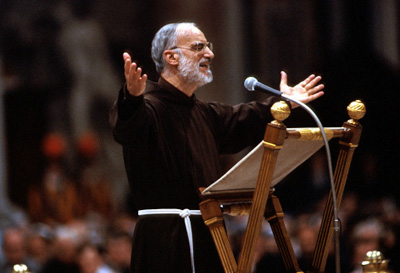

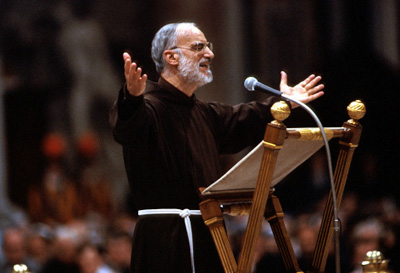

Raniero

Cantalamessa and the Call for a New

Evangelization

Part

1 –

Proclaiming

the Kerygma in the Power of the Holy

Spirit

By

Sue Cummins

Note: The

following article is adapted from the

thesis, Raniero

Cantalamessa and the New

Evangelization: Proclaiming

the Kerygma in the Power of the Holy

Spirit, which was submitted to the

School of Theology of Sacred Heart Major

Seminary, Detroit, Michigan USA,

December 2014. Sue

Cummins works full time for the

Archdiocese of Detroit’s Department of

Evangelization and Catechesis as Regional

Catechetical Coordinator.

Introduction

A

simple Franciscan friar made a decision over

thirty years ago to leave his academic post

and dedicate his life to preaching. Since that

time he has impacted the lives of thousands of

men and women all over the world with his

preaching, teaching and writing. Father

Raniero Cantalamessa’s writings, sermons, and

the example of his life offer wisdom,

inspiration, and practical guidance for those

seeking to respond effectively to the call for

a new evangelization.

According to Cantalamessa, the

fundamental rule of evangelization is to

proclaim the gospel message (the kerygma) in

the power of the Holy Spirit.[i] He asserts that the kerygma

should be the essential content of preaching

and that “preaching in the power of the Holy

Spirit” should be the method of

proclamation.[ii]

This paper will explore the

importance of Cantalamessa’s message for the

new evangelization and consider the advice

that he gives to those who are called to

teach and preach the word of God.

Cantalamessa’s emphasis on the importance of

preaching the kerygma in the power of the

Holy Spirit, while being firmly rooted in

the Tradition of the Church, is a prophetic

word for our times. Cantalamessa’s plentiful

references to Sacred Scripture and to the

writings of the Church Fathers provide an

entry point to the rich traditions of the

Church. His message is indispensable to the

success of those who hope to make a

significant contribution to the new

evangelization.

The Call for a New

Evangelization

Evangelization has been at the

heart of the Christian mission since the

time of Jesus and the first Apostles. Jesus’

last words before ascending to heaven

consisted of a mandate to evangelize: “Go

therefore and make disciples of all nations,

baptizing them in the name of the Father and

of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Mt

28:19).[iii]

Throughout his career as a

preacher Cantalamessa has consistently

spoken of the need for a new evangelization.

At the opening address of the 2005

International Alpha Conference Cantalamessa

spoke about a “presence-absence of Jesus in

our time.” He pointed out that in secular

society many books, television shows, and

movies exploit Jesus for the purpose of

lucrative gain, while people of faith do not

always recognize his importance. Cantalamessa said that

Christ is present in our culture, but he is

often absent or even excluded from the lives

of many who call themselves Christians.[iv] Many people believe in some

kind of a Supreme Being who created the

world and that there is some kind of life

beyond death, but they do not have Christ as

the object of their faith: “Sociological

surveys point to this fact even in countries

and regions of ancient Christian tradition,

like the one where I was born in central

Italy. Jesus is practically absent in this

kind of religiosity.”[v]

Cantalamessa often makes

reference to sociological surveys; there are

many statistics available that back up and

illustrate his thesis. Sherry Weddell makes

some very compelling observations about

research that has been done on religious

belief in the United States.[vi]

Based on an analysis of data available

through the Pew Forum on Religious and

Public Life (2008) she points out that

religious identity in the United States is

very fluid: “53 percent of American adults

have left the faith of their childhood at

some point; 9 percent have left and

returned.”[vii]

The data shows that those who identify

themselves as unaffiliated are the

“fastest-growing religious demographic” in

the United States – one in every six

Americans.[viii] Of

self-identified Catholics only 48 percent

are sure that it is possible to have a

personal relationship with God.[ix]

Through her work with Catherine of Siena

Institute[x]

Weddell has had an opportunity to meet with

and interview thousands of Catholics from

across the United States, many of them

serving as parish and diocesan leaders. She

and her colleagues have asked many of them

to describe their “lived relationship with

God.” Weddell points out that many of the

Catholics who are asked to describe their

relationship with God are unable to do so:

The majority of

Catholics in the United States are

sacramentalized but not evangelized. They do

not know that an explicit personal

attachment to Christ – personal discipleship – is normative Catholicism as taught

by the apostles and reiterated time and time

again by the popes, councils, and saints of

the Church.[xi]

Weddell’s

experience of working with Catholics across

the United States has led her to the

conclusion that “few Catholics have ever

heard of the kerygma . . . and even fewer

know what the kerygma contains or have heard

it preached clearly.”[xii]

The statistics

relating to youth and religious belief are

even more sobering. The National Study of

Youth and Religion (NSYR)

that was

conducted between the years 2003 and 2005

examined the spirituality of adolescents

in the United States. The findings of this

study were reported by Christian Smith in

a book he co-authored with Melinda Lundquist Denton.[xiii] Smith

observes that most of the adolescents

interviewed in the study said that they

believed in God and they identified their

faith as being the faith of their parents.[xiv] Further questioning revealed that

many who identified themselves as

religious, when asked about specific

beliefs, said that they did not have any. Of

those who said they held specific beliefs,

very few were able to describe them. [xv]

Most teens interviewed did not believe in a

Triune God; they did not embrace the gospel

of the incarnate Jesus, Son of God,

crucified and raised from the dead. Thomas

V. Sanabria used the data from NSYR to

compare the religious beliefs held by

Catholic youth to those held by Protestant

youth. His analysis indicates that Catholic

youth were less grounded in the basic tenets

of Christianity than their Protestant

counterparts.[xvi]

Smith contends that “the

de-facto dominant religion among

contemporary U.S. teenagers is what might be

called ‘Moralistic Therapeutic Deism

(MTD).’”[xvii]

Smith describes the basic tenets of this MTD

“religion” as a creed that consists of the

following tenets of faith:

1.

A God exists who created and

watches over life on earth.

2. God wants people to be good,

nice, and fair to each other.

3. The central goal of life is

to be happy and to feel good about oneself.

4. God

is not particularly involved in one’s life

except when needed to resolve a problem.

5. Good people go to heaven

when they die.[xviii]

Further analysis of the data

from the National Study of Youth and

Religion as it relates to Hispanic youth,

along with the results of further study and

supplementary interviews, shows that

Hispanic teens are not immune to MTD.

Fourteen out of the sixteen Hispanic youth

who were interviewed in supplemental

interviews held to the tenets of MTD,

confirming the findings of the National

Study. [xix]

Kenda Creasy Dean revisited the

results of the National Study of Youth and

Religion.[xx] She writes that the evidence of

the NSYR indicates that not only teenagers,

but also many congregations of adults that

call themselves Christian are “almost

Christian”:

After two and a

half centuries of shacking up with “the

American dream,” churches have perfected a

dicey codependence between consumer-driven

therapeutic individualism and religious

pragmatism. These theological proxies gnaw,

termite-like, at our identity as the Body of

Christ, eroding our ability to recognize

that Jesus’ life of self-giving love

directly challenges the American gospel of

self-fulfillment and self-actualization.[xxi]

Dean

recognizes the need for “nurturing a

bilingual faith” that includes an ability to

communicate with those who are converted and

well-versed in Christianity, and an aptitude

for speaking with those who are not well

versed in the Christian faith. She is

concerned that many churchgoers have not

heard the Gospel presented to them in a way

that they can make it fully their own. She

sees a need for youth leaders and other

church members to learn how to communicate

in the language of global postmodern secular

society in order to translate and

effectively pass on the truths of our

Christian faith.[xxii]

While

most of the statistics cited thus far are

related to religion in the United States, it

is worth noting that Europe is even further

down the path of secularization. In his

essay “Evangelization of Europe?

Observations on a Church in Peril,” Peter

Hunermann cites some sobering statistics

that illustrate the decline of numbers of

those involved in the Church in Europe, and

the shrinking numbers of men and women who

identify themselves as Christian.[xxiii] He

points out that behind the decline in

numbers there is an even more important

shift in the worldview held by the greater

part of the population. Hunermann

presents the thesis that the crisis of the

Church in Europe is related to the

“discontinuity” that exists between the

tenets of modernity and the Church.[xxiv] He

makes a valid point that one of the reasons

for the crisis in the Church is the drastic

change that has come about in the attitudes

and the practices of modern society.

Cultural Trends and

Challenges to Evangelization

Cantalamessa is very aware of

the challenges that modern society presents

to evangelization. In a series of Advent

sermons given to the papal household in

2010,[xxv] he identifies three cultural

trends of our modern age that contribute to

the state of the present-day Church:

scientism, secularism, and rationalism –

all

leading to relativism. In his first Advent sermon he

outlines four main theses of scientism:

1. Science, and in particular

cosmology, physics and biology, are the only

objective and serious ways of knowing

reality.

2. This way of knowing is

incompatible with faith that is based on

assumptions which are neither demonstrable

nor falsifiable.

3. Science has demonstrated the

falsehood, or at least the lack of necessity

of the theory of God.

4. Almost the totality or at least

the great majority of scientists are

atheists.[xxvi]

Cantalamessa points out that,

contrary to the fourth tenet, many

scientists believe in God, often as a result

of their scientific analysis. Still, the

influence of atheistic scientists on modern

thought should not be underestimated.[xxvii] Of particular concern to

Cantalamessa is the denial of the importance

and uniqueness of human beings in the

created world that leads to a trivialization

of their role and of the centrality of Jesus

Christ as God made man. He sees

non-believing scientists, biologists and

cosmologists in particular to be in

competition with one another to see who can

go furthest in “affirming the total

marginality and insignificance of man in the

universe and in the great sea of life

itself.”[xxviii]

The second Advent sermon deals

with the problem of secularism. Cantalamessa

explains that the words secular and

secularization can be used in a variety of

ways and that their connotations are not

always negative:

Secularization is a complex and

ambivalent phenomenon. It can indicate the

autonomy of earthly realities and the

separation between the Kingdom of God and

the kingdom of Caesar and, in this sense,

not only is it not against the Gospel but

finds in it one of its profound roots;

however it can also indicate a whole

ensemble of attitudes contrary to religion

and to faith; hence, the use of the term

secularism is preferred. Secularism is to

secularization what scientism is to

scientific nature and rationalism to

rationality.[xxix]

Secularism

with its focus on the here and now diverts

the attention of men and women away from the

importance of eternal truths. It results in

a life that is oriented around the material

world where spiritual realities are ignored

or denied. There is no reference to a

transcendent God who is creator and

sustainer of all life; there is no fear of a

final judgment or anticipation of eternal

happiness that surpasses any happiness that

could be known in this life. Life revolves

around experiencing pleasure and avoiding

pain.

According

to Cantalamessa, the nineteenth century saw

a decline in the belief in eternal life:

“Little by little, suspicion, forgetfulness

and silence fell on the word eternity.

Materialism and consumerism did the rest in

the opulent society, making it seem

inconvenient to still speak of eternity

among educated persons.”[xxx]

Today even Christians have lost focus on

spiritual realities; those Christians who do

believe in eternal life rarely speak of it.

Many have a very vague or distorted picture

of what Sacred Scripture teaches about the

spiritual world and the life that awaits

them beyond the death of their bodies.

Cantalamessa recognizes the negative effect

that secularism and the lack of concern

about eternal life has on Christian faith:

The fall of the horizon of

eternity, or of eternal life, has the effect

on Christian life of sand thrown on a flame:

it suffocates it, extinguishes it. Faith in

eternal life is one of the conditions of the

possibility of evangelization. “If for this

life only we have hoped in Christ, we are

the most pitiable people of all,” exclaims

St. Paul (1 Corinthians 15:19).[xxxi]

There

are different versions of secularism. The

NSYR aptly illustrates the current version

of secularism that is prevalent in the

United States. This version recognizes the

existence of God and looks to some kind of

life after death, but it fails to recognize

the possibility that entering paradise may

require more than being a “nice person.” The

need to repent of sin and to live according

to the gospel is not recognized. There is a

lot of confusion about moral living; most of

life is taken up with concern for fulfilling

temporal needs and desires.[xxxii]

Cantalamessa

ends his Second Advent sermon with the

reminder that there is life after death and,

whether they realize it or not, all men and

women will live forever. He unabashedly

points out that it is important to

understand that the nature of eternal life

will not be the same for all: “the passage

from time to eternity is not straight and

equal for all. There is a judgment to face

and a judgment that can have two very

different results, hell or paradise.”[xxxiii]

Many who call themselves Christians have not

really understood and embraced the truth

about God and what is necessary for

salvation. Many do not even call themselves

Christians. Regardless of religious beliefs

or lack of belief, all will one day stand

before the Lord Jesus Christ awaiting

judgment. All will live forever, but not all

will live forever in the joy of full

communion with their creator.

It is important, therefore, to

realize the high stakes involved in the call

to evangelize. Motivation to evangelize

wanes when there is no proclamation of the biblical

truths regarding heaven and hell. Ralph

Martin points out that the watering down of

these biblical truths led to a decline of

evangelization after Vatican II. He says

that these truths need to be stated clearly

in order to motivate those called to

evangelize:

The reasons

for the command [to evangelize] – namely, that the eternal destinies

of human beings are really at stake and for

most people the preaching of the gospel can

make a life-or-death, heaven-or-hell

difference – need to be unashamedly stated. This

is certainly why Jesus often spoke of the

eternal consequences of not accepting his

teaching – being lost forever, hell – and did not just give the command

to evangelize.[xxxiv]

This does not mean that the

evangelist always confronts secularism with

arguments laced with fire and brimstone. The

love and mercy of God, the saving grace of

Jesus, and the joy of life in the Holy

Spirit are biblical truths that need

emphasis in our day.

The message of the existence of

a loving God who longs for a relationship

with human beings who were created in love

is an attractive and compelling message. Cantalamessa

points out that there is an inner longing

for life beyond this life that is intrinsic

in all human beings. Presenting a positive

view of life after death and living a life

that is permeated with resurrection hope is

an important aspect of evangelization: “As

for scientism, speaking also of secularism,

the most effective answer does not consist

in combating the contrary error, but in

making shine again before men the certainty

of eternal life, appealing to the intrinsic

force that truth possesses when it is

accompanied by the testimony of life.”[xxxv]

Cantalamessa addresses the

obstacle of rationalism in his final Advent

sermon of 2010.[xxxvi]

The problem of rationalism is a distorted

view of reason that makes reason supreme,

higher even than God and spiritual realities

that cannot be contained by reason.

Rationalism insists that actions and beliefs

should be governed by reason alone, and that

reason is the primary source of knowledge

and truth. Cantalamessa is not denying that

reason is important; he recognizes that as

Christians we are called to use our reason

and that reason is not in conflict with

faith. His point is that reason cannot reign

supreme over God and that without

recognition of the power and sovereignty of

God, reason falls short.

Cantalamessa echoes St. John

Paul II, who wrote about the relationship

between faith and reason in his encyclical

letter Faith and Reason, Fides et Ratio, promulgated

in September 1998. In this encyclical St.

John Paul II states that there is “no reason for

competition of any kind between reason and

faith: each contains the other, and each has

its own scope for action” (FR,

17). Reason has its place but reason alone

is not sufficient:

The world and all that happens

within it, including history and the fate of

peoples, are realities to be observed,

analyzed and assessed with all the resources

of reason, but without faith ever being

foreign to the process. Faith intervenes not

to abolish reason's autonomy nor to reduce

its scope for action, but solely to bring

the human being to understand that in these

events it is the God of Israel who acts.

This is to say that with the light of reason

human beings can know which path to take,

but they can follow that path to its end,

quickly and unhindered, only if with a

rightly tuned spirit they search for it

within the horizon of faith. (FR,

16)

The

artificial attempt to separate faith and

reason takes away from the God-given

capacity of human beings to understand the

truth about the world and its Creator.

Cantalamessa

calls our attention to an address that John

Henry Newman gave at Oxford University in

December of 1831, entitled “The Usurpations

of Reason.”[xxxvii]

Newman pointed out several instances where

reason had been allowed to rule outside of

the appropriate scope of its authority. For Cantalamessa, the

title of Newman’s address, “The Usurpations

of Reason,” illustrates an understanding of

the negative effects of distorted

rationalism:

In a note of

comment on this address, written in the

preface to its third edition in

1871, the author explains what he intends

with such an expression. Understood by

usurpation of reason is “a certain popular

abuse of the faculty, viz., when it occupies

itself upon religion, without a due familiar

acquaintance with its subject-matter, or

without a use of the first principles proper

to it. This so-called Reason is in Scripture

designated 'the wisdom of the world'; that

is, the reasoning about Religion based upon

secular maxims, which are intrinsically

foreign to it. [xxxviii]

In Newman’s scenario reason

takes an “imperialistic” role over religious

beliefs; all actions and beliefs must submit

as subjects to reason. Cantalamessa proposes

an additional political metaphor, that of

isolationism, as an example of an alternate

way in which rationalism distorts the use of

reason:

Newman's analysis has new and

original features; he brings to light the so

to speak imperialist tendency of reason to

subject every aspect of reality to its own

principles. One can, however, consider

rationalism also from another point of view,

closely connected with the preceding one. To

stay with the political metaphor used by

Newman, we can describe it as the attitude

of isolationism, of reason's shutting itself

in on itself. This does not consist so much

of invading the field of another, but of not

recognizing the existence of another field

outside its own. In other words, in the

refusal that some truth might exist outside

that which passes through human reason.[xxxix]

Cantalamessa is referring here

to the widespread tendency to recognize as

real only that which can be proven by the

scientific method; anything beyond the scope

of scientific proof is ignored or denied.

Another aspect of the

usurpation of reason relates to morality.

Newman points out that the moral principles

of human beings are not necessarily tied up

with their intellectual principles. A very

intelligent person who possesses a great

ability to exercise reason might lead a

deplorable moral life.[xl]

Reason can be used as a tool for religious

purposes, and reason may sometimes lead to

religious truths, but religious truths do

not need to be established by rational proof

the way that the laws of physics might be

subjected to the scientific method.[xli]

Religious beliefs are not subordinate to

reason as their imperial ruler. According to

Fides et Ratio, when we are

dealing with God, the truth about God, and

the way of life that God wants for his

people, we are dealing with something that

goes beyond reason:

On the basis of this deeper

form of knowledge, the Chosen People

understood that, if reason were to be fully

true to itself, then it must respect certain

basic rules. The first of these is that

reason must realize that human knowledge is

a journey which allows no rest; the second

stems from the awareness that such a path is

not for the proud who think that everything

is the fruit of personal conquest; a third

rule is grounded in the “fear of God” whose

transcendent sovereignty and provident love

in the governance of the world reason must

recognize. (FR, 18)

Cantalamessa combines the

elements of Newman’s analysis by showing

that the cultural trends of scientism,

secularism, and rationalism lead to another

obstacle to evangelization – relativism. There are different

forms of relativism. Protagorean relativism

holds that what is perceived is true to the

person who perceives it and that truth does

not exist independently of what the

perceiver says is true. There are no

objective standards that can be used to

determine truth; knowledge and sense

perception are relative to the perceiver. A

saying attributed to the Sophist Protagoras

describes the mentality of many modern men

and women: “Man is the measure of all

things; of things that are that they are;

and of things that are not that they are

not.”[xlii]

The lack of conviction among so

many people that there exist objective

standards of truth makes it difficult to

appeal to natural law or to revelation as a

measure of truth. The danger is that

individuals without a conviction that truth

exists will not search for truth; they may

not concern themselves with the existence of

God and God’s will for their lives. In a

Christmas address given to the Roman Curia

in December, 2009, Pope Benedict XVI spoke

about the importance of keeping the search

for God alive: “As the first step of

evangelization we must seek to keep this

quest alive; we must be concerned that human

beings do not set aside the question of God,

but rather see it as an essential question

for their lives. We must make sure that they

are open to this question and to the

yearning concealed within it.”[xliii]

Acutely aware of the difficulty

of the task that the Church faces in

responding to the call to the new

evangelization – within and without –

Cantalamessa,

like Newman, advises his listeners to

maintain hope and joy. He

points out that it is important to be aware

of the challenges but expedient to avoid

negativity or despair and to recognize the

many signs of God’s presence in the world.[xliv] He

points to the many positive things happening

in the Church: the outpouring of charisms;

the increased participation of the laity in

parishes and lay movements; the Catholic

organizations and individuals who are

dedicated to the care of the poor; those who

have been martyred for their faith; the

“holy” and “learned” Popes who have served

the Church for the past century and a half;

the desire for unity and the progress made

in ecumenical relations.[xlv] Cantalamessa

speaks openly about the difficulties in the

world and in the Church, but he also

provides encouragement and his message is

full of hope. He

offers many insights into the content and

the methods that are necessary for the

success of the new evangelization. The next

chapter will explore Cantalamessa’s message

about the content of the Christian message

and the need to proclaim the kerygma, the

good news of salvation in Jesus.

|

Sue

Cummins is a member of Word of

Life Community and Bethany

Association. She lives in

Detroit, Michigan USA and

teaches as part-time faculty at

Sacred Heart Major

Seminary. Susan has a

concentration in spirituality

with a focus on the work of St.

Ignatius and St. John of the

Cross. She worked for fifteen

years as part of an

international mission team

giving retreats, training, and

spiritual direction to leaders

of Christian communities in

Central America, Mexico, Spain,

Europe, and the Middle

East. She has over ten

years of experience working with

youth as senior staff with

University Christian Outreach

(UCO) and Youth Works Detroit

and as a high school

teacher. Susan is fluent

in Spanish. She worked as

director of a bi-lingual

Religious Education Program at

St. Gabriel Catholic Church in

Southwest Detroit from 2005 to

2012. Sue has recently

been hired to work full time for

the Archdiocese of Detroit’s

Department of Evangelization and

Catechesis as Regional

Catechetical Coordinator.

|

Footnotes

[i] Raniero Cantalamessa, The Mystery of God’s Word, trans.

Alan Neame (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical

Press, 1994), 54. Tanslated from Chi

ha parlato nel Figlio: Il mistero

della parola di Dio (Milan:

Editrice Ancora , 1984).

[iii] All

biblical citations are from the New

Revised Standard Version unless

otherwise indicated.

[iv] Cantalamessa, “Faith Which

Overcomes the World,” Opening Address

for the International Alpha Conference,

June 2005 (London: Alpha International,

2005), 2.

[vi] Sherry Weddell, Forming

Intentional Disciples: The Path to Knowing and

Following Jesus (Our Sunday Visitor:

Huntington, IN, 2012).

[ix] Sherry Weddell, Forming

Intentional Disciple, 44.

[xi] Weddell, Forming

Intentional Disciples, 46.

[xiii] Christian Smith and

Melinda Lundquist Denton, Soul

Searching: The Religious and Spiritual

Lives of American Teenagers (New

York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[xiv] Smith

and Denton, Soul Searching, 122.

[xv] Ibid., 132-33.

[xv] Sherry Weddell, Forming

Intentional Disciples: The Path to Knowing and

Following Jesus (Our Sunday Visitor:

Huntington, IN, 2012).

[xv] Ibid.,

19.

[xv] Ibid.

[xv] Sherry Weddell, Forming

Intentional Disciple, 44.

[xv] Website for Catherine of Siena

Institute, accessed December 3, 2014, http://www.siena.org/.

[xv] Weddell, Forming

Intentional Disciples, 46.

[xv] Ibid., 67.

[xv] Christian Smith and

Melinda Lundquist Denton, Soul

Searching: The Religious and Spiritual

Lives of American Teenagers (New

York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[xv] Smith

and Denton, Soul Searching, 122.

[xv] Ibid., 132-33.

[xvi] Thomas

V. Sanabria, “Personal Religious Beliefs

and Experiences,” in Pathways of Hope and

Faith Among Hispanic Teens: Pastoral

Reflections and Strategies Inspired by

the National Study of Youth and

Religion,

ed. Ken

Johnson-Mondragon (Stockton,

CA: Instituto Fe

y Vida, 2007),

41-79. For

example 43% of Hispanic and 47% of white

Catholics definitely believed in life

after death compared to 53% of Hispanic

Protestants and 58% of white

Protestants. Of Hispanic

Catholic youth 70% believe in a judgment

day; white Catholics score lower at 66%

compared to Hispanic Protestants at 92%

and white Protestants at 82%. When asked

about reincarnation, 15% of the Hispanic

Catholic youth in the study believed in

reincarnation as did 14% of white

Catholics; this compares to 5% of

Hispanic Protestants and 8% of white

Protestant youth.

[xvii] Smith and Lundquist, Soul Searching,166.

[xix] Johnson-Mondragon, Pathways of Hope, 73.

[xx] Kenda Creasy Dean, Almost Christian: What the

Faith of Our Teenagers is Telling the

American Church (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2010).

[xxii] Creasy

Dean, Almost Christian, 112-30. See also a paper

written by Edwin Hernandez with Rebecca

Burwell and Jeffery Smith, “A Study of

Hispanic Catholics: Why Are They Leaving

the Catholic Church? Implications for

the New Evangelization,” in The

New Evangelization, 109-142.

[xxiii] Peter

Hunermann, “Evangelization of Europe?

Observations on a Church in Peril,” in Robert J. Schreiter,

ed., Mission in the Third

Millennium (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis

Books, 2001), 57-80.

[xxv] Cantalamessa’s Advent

sermons and other sermons and articles

written by him can be found on his

website, accessed

December 3, 2014, http://www.cantalamessa.org.

[xxix] Cantalamessa,

“2nd Advent Sermon, 2010.”

[xxx] Cantalamessa,

“2nd Advent Sermon, 2010.”

[xxxii] Smith

and Lindquist, Soul

Searching, 163.

[xxxiii] Cantalamessa,

2nd Advent Sermon, 2010.

[xxxiv] Ralph Martin, Will Many Be Saved? What

Vatican II Actually Teaches and Its

Implications for the New

Evangelization (Grand Rapids: W. B.

Eerdmans Publishing, 2012),

204.

[xxxv] Cantalamessa,

2nd

Advent Sermon, 2010.

[xxxviii]

Cantalamessa, 3rd Advent Sermon, 2010.

Newman’s quote is

from Oxford University Sermons, London, 1900, 54-74.

[xxxix] Cantalamessa,

3rd Advent Sermon, 2010.

Newman’s quote is

from Oxford University Sermons, London, 1900, 54-74.

[xl] Newman,

“The Usurpations of

Reason.

[xli] See Fides et

Ratio 42: “Reason in fact is not

asked to pass judgment on the contents

of faith, something of which it would be

incapable, since this is not its

function. Its function is rather to find

meaning, to discover explanations which

might allow everyone to come to a

certain understanding of the contents of

faith.”

[xlii] Peter

A. Angeles, The Harper

Collins Dictionary of Philosophy

(Harper Collins: NY, 1992), 261.

|